Death by a Thousand Cuts, Part 3

Doom and distraction? Seeing and making the same, old strategic mistake.

Still thinking about how I’ve been too busy putting out fires to build something that doesn’t involve my expertise in areas like cognitive bias, methodological mistakes, and difficult diagnoses. This expertise started as helping family, friends, and myself not die. Lately I’ve been wondering what this might mean in social and political terms as I try to connect different contexts in a bigger picture. I realize that I’m rabbit-holing putting out these fires — going deep into specialist literatures — probably less well than other people are in the course of putting out other fires like climate emergency. But we all do it. And I’m thinking that maybe the way we think and teach how to think about problems and their solutions (science) itself is the problem. It doesn’t help to put out all these fires if we don’t teach people to stop throwing lit cigarettes into the forest. So we need to work on the source of these problems, as well. This is the beginning of my thinking about this, and I see some patterns I want to hash out and share. Please forgive my ignorance and write me if you have thoughts about this. This post does doom; the next looks more hopefully at possible solutions.

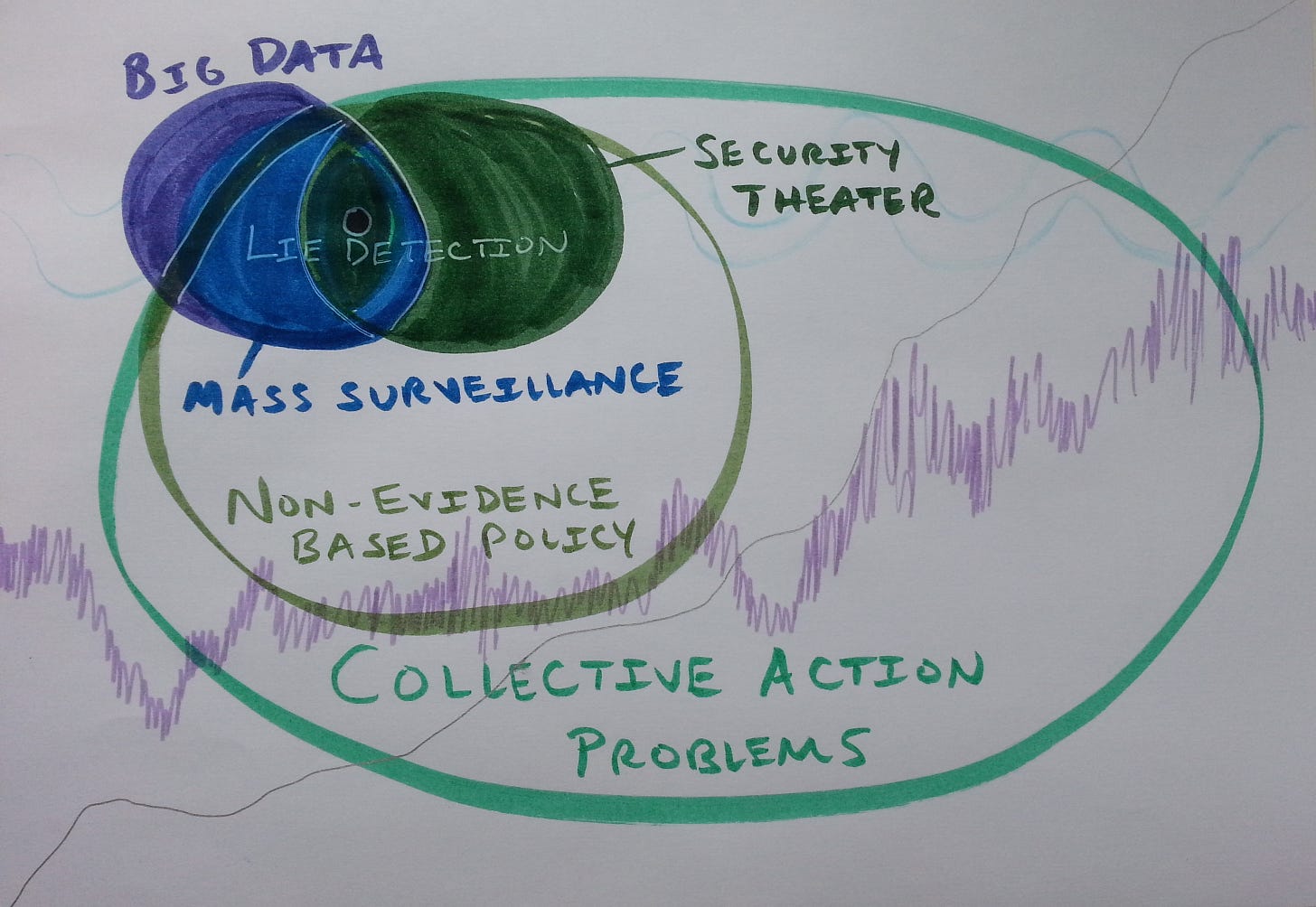

Last week I wrote about how the world is burning, a lot of people are too busy putting out various fires caused by bad science to stop it, and this is a collective action problem. In fact, it’s arguably the collective action problem of complex societies needing more and better public interest science (including science education, science communication, and science policy) to make better policies generally to solve all specific collective action problems nested within the biggest one, which I see as the classic “might ain’t right.” Because I am a simple girl who likes to draw pretty pictures, this reminds me of the nested Venn Diagram that summarized a talk I gave a while back on a different case study within the non-evidence-based policy sphere in this context — lie detection.

More recently I’ve been publishing on breastfeeding, an eerily (to me) similar case study in many ways. In both cases, a wall-to-wall façade of pseudoscientific bullshit props up an entire industry doing the exact opposite of its explicit goal: Finding the truth — by lying; protecting babies and women — by hurting them. The naturalistic fallacy underpins both: Bodies know best, are good and true — no mistakes in nature. (Spoiler alert: Nature is a bitch.) The big difference is that my latest obsession is nested in with other case studies of stuff that may cause substantial increases in developmental risks to kids from moms’ medical choices, which is adjacent to women’s health and nested in other harm from medical intervention (iatrogenesis), which is nested in other science policy screw-ups, within other collective action problems, within might not equalling right.

Admittedly, this is an anti-authoritarian way to see the world. It assumes resisting illegitimate authority is the solution to a lot of our problems, though most problems have multiple causes. Speaking of multi-causality…

Back in narrower terms where I’ve spent a lot of time lately, parents want to have healthy kids, and there are lots of possible contributing factors to increased risks for permanent disabilities — so there are lots of things they could do to reduce these risks, if they had more information. But those things are spread out across lots of areas. Information about relevant risks is specialized (in different subfields and their dialects, so generalists aren’t putting together the pieces), siloed (published in subfield academic journals, often not publicly accessible without tricks), and scientific (in need of translation from a specialist context for a broader audience). Putting it all together is a public good provision that science should be doing.

But there is no science. At least, not with a capital-S and a return address. Rather, there are only human beings struggling to remember to buy milk, doing their best amid conditions of increasing precariousness to balance competing demands on limited resources. There are fractal bits of the big science problem any one person could potentially focus on, and institutions incentivize focusing really narrowly. You have to get down in the weeds on case studies to do this work properly. But then you have to come back to the surface to tell people what’s there, and ideally, connect cases in ways that make sense to ordinary people across very different realms, so you reach outside of isolated echo chambers with the bigger story and it helps more people. This is tough.

Example: I did a deep dive on the jaundice-autism literature, sparked by a recent meta-analysis that got it demonstrably wrong and recommended a continuation of medical practices that may seriously endanger newborns, including by substantially increasing risks of long-term neurodevelopmental disorders like autism. I’m proud of my nitty-gritty work, and tried to write as if I was talking to the parents and practitioners whom my findings impact. But in the reality of who reads medical journal articles and their finer methodological points, I was really writing to the methodologists whose work I applied to critically synthesize existing meta-analyses. It’s great that I needed to know the truth, found it as best I could, and learned a lot along the way. But that was only half the job. Now I need to find the right editor and platform to translate this and other rabbit-holing breastfeeding research offshoots for a popular audience. What makes the issue broader interest to me is the connection to common methodological mistakes across medicine and science. But what will make it broader interest to others? And how long will I spend on what was one offshoot of an easily possible dozen within a small subset of problems within problems within problems? What’s the opportunity cost?

It’s not clear how to solve this larger problem — the collective action problem of propaganda science, or, death by a thousand cuts. It would be a separate conversation to talk about all the ways normal internal scientific correction mechanisms are malfunctioning (see, e.g., the most recent revelations about how medical publishing ethics group COPE is brokedy-broke-broke), people “doing their own research” also might not be the answer, top-down solutions promising value-free science (the Master Science, as it were) have a grotesquely abysmal history, selective efforts to reform scientific practices from within face structural hurdles that doom them to failure within the window when the planet/species/civilization needs success, and backlash denying the problem is just crazy. I’ll return to possible solutions in a future post.

Most activists I know who have remained relatively sane have bitten off small chunks of work they consider theirs. Sometimes they can make inroads that way. But what does it do to them?

Periodic burnout is common. It seems to be cognitively and emotionally harder to live outside the “just world” story that feels good, and in the unjust world that needs people who resist illegitimate authority instead of serving it. So you pay a price for telling yourself the truth before you even start paying socially and professionally for telling other people things they don’t like hearing, too. But it doesn’t matter because it’s probably not a choice, in my view, so much as a constitutional element. You are this kind of person, or you’re not. It probably has neurodivergence, personality structure, and experience elements, and it takes all kinds.

Caveat: I’m bad at gaming anything out in real life. A game theorist without game — woe unto the anti-hero. One of the main failures, I notice, in my projections is how unpredictable emotional reactions color material realities in unpredictable ways. So when I win, or at least take my least bad shot, I sometimes lose; and vice-versa. And, from the imperfect yet easier outside looking into other people’s lives, it sure looks like other people do this, too. Especially when fear keeps us from thinking properly, we tend to destroy what we seek to protect. Because we lose our own signals.

So there’s the caveat; now here’s the scheming: Maybe it’s worth connecting the need for better public interest science at all levels (from research to policy and communication), with the crises we all face. From climate change to the autism epidemic, we need better science to challenge propaganda with truth. What might that look like?

My rough cut within this rough cut: What if science communication taught methods to the segment of the general public that can be interested in this — not just offering takeaway points on specific scientific topics, as usual? Otherwise it risks repeating the mistakes of the last generation of anti-authoritarian scientist-activists who crashed and burned by treating injustice as an information problem when it’s not one. It’s an information-encoding, sense-making, source-weighing problem, instead. Stories, not data. And story-telling, not one story.

Otherwise, the effects of the great many inconvenient truths that shape our lives may keep us too busy to protect ourselves, our children, and life as we know it on our planet. Death by a thousand cuts looks like many different problems, with everyone interested in their own, by necessity. Poof, finite resources are gone.

In this envisioning, it’s the commons of the truth, which is largely about our ability to think critically about information from various sources, that needs regreening. You don’t do that with narrow topic focus, which is counter-intuitive to most activists. That’s exactly how collective action problems don’t get solved. Tragically (in the tragedy of the commons sense), all the incentives are stacked in that direction. I get it — world on fire, put out your little fire. But what if that’s the way the whole forest burns down?

Then we need to face the big truth problem. We’re eternally divided and conquered, with activism focusing primarily narrowly on issue areas that detract from attention to the big science (research, policy, communication, education) problem. Bourdieu would call this reproducing social and cultural error, like institutions always do. But what if we can’t exit that reproduction because all creativity is synthetic, we’re hard-wired to be prone to making certain mistakes, we’re social and political animals bound to our contexts, and there’s too much on fire all at once to put it all out — we have to be selective?

That would seem to to suggest we’re screwed, in technical terms. Society got away from itself in complexity on a finite planet that won’t forgive the lag between how fast we make mistakes and how fast we recognize them. Activists will always struggle rightly with what level of specificity to tackle. The bigger picture will always suffer when we get something smaller done. That will burn finite resources that are needed elsewhere to put out fires. But we have to satisfice (take our best shot with limited information) to get something done, instead of optimizing (trying to take a better / closer to best shot with better / closer to complete information), also for rational reasons of limited resources. This is how the world burns.

It’s also how most people make most decisions that work out fine most of the time. We just care a lot about the ones that don’t sometimes, like when they could have killed or maimed us, our friends, our parents, or our kids. Or did.

This seems to have been my way of working myself up to being off the hook in the biggest big pictures, for now. No saveable world means that doing what you can to improve some people’s quality of life makes sense. Sure, I could try to conceive of a massive science education project to help people understand stuff I’m constantly learning more about as a still-young scientist myself (pushing 40). Then better science might save the world! It’s easy to dismiss such a possibility as naive or unlikely. But it’s not obvious, to me at least, that there’s a better option.

So for now I think about the big picture that affects all of us deeply. But work in the weeds I know and love. Finding my rabbit holes and diving down as much as possible, because that’s what a brain like mine is good at doing — in contrast to all the more normal things it’s not. This seems to be a deadly mistake in the big picture. I see that. But choose it anyway, not seeing a better way to do what I need to do. A little humble pie never hurt anyone, doomed world notwithstanding.