The AI Act Proposes to Limit Dangerous Tech

But the usual suspects want to carve out the usual security exemptions

We’ve all been there: A friend has had too much to drink and goes for the car keys. When it’s Ann, who did ballet with you in grade school, you take the keys and guide her steadily to your sofa. But when it’s Steve, who played rugby in college and disagrees with your assessment, it’s not so easy. It takes a few more people taking a bit more time, making a bit more noise, to convince him. And it’s not sure to work.

This is what’s happening with European tech legislation right now. Recently I explained why proposed digital communications scanning program Chat Control is a spectacularly bad idea according to probability theory. Like possibly all mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems, it’s doomed to backfire and undermine security by generating excessively large and damaging numbers of false positives while missing non-negligible numbers of false negatives, burning finite resources on bad pay-offs under conditions of real-world inferential uncertainty.

Experts from many different domains are in somewhat broad agreement that Chat Control is dumb, so there’s at least a chance it will die a well-deserved death. Unlike its UK analogue, the Online Safety Bill, which the UK Parliament appears set to push through with no discussion of the relevant math. This will breaking encryption to do client-side scanning of essentially all digital communications, degrading privacy worldwide, and is stupid even if all you care about is security.

The other big EU tech bill on the horizon is the AI Act, and it’s… Complicated. Europeans are trying to lead the world in limiting dangerous technologies, but it’s not clear their leaders will let them. They’re big guys, and we can’t necessarily make them sleep on the sofa. Would that they understood it’s for their own good (and everybody else’s).

This Is What Democracy Looks Like

The AI Act’s status: Last month, the members of the European Parliament adopted negotiating positions. It would be the world-first comprehensive AI law, fulfilling Europe’s counterbalancing role against U.S., Russian, and Chinese human rights infringements. Member states aim to agree on the terms by the end of the year. What are the terms of those terms?

The draft AI Act the European Parliament put out last month would ban emotion-recognition AI, real-time biometrics and predictive policing in public spaces, and social scoring. These bans are good ideas. Tech that reads internal states, like emotions or truthfulness/deception, doesn’t exist; and if it did, it would be the end of human rights. Doing mass security screening for low-prevalence problems — like real-time emotion-recognition, biometrics, and predictive policing in public spaces do — is mathematically doomed to fail. And social scoring — giving people a score in terms of some nebulous positive value like trustworthiness (Western) or obedience (Chinese) on the basis of a wide range of data on social behavior that may include online, educational, financial, and other miscellaneous doings — is just a sloppy name for a sloppy practice that makes judging people look more sciencey than it is.

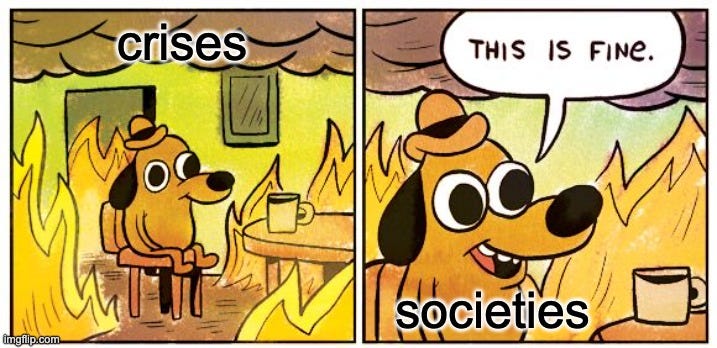

So on one hand, the latest version of the AI Act is good news. On the other hand, this draft of the AI Act is going to change as the usual suspects carve out the usual security exemptions. What can scientists and activists hope for in the diplomatic melee? Are there real chances to save some of these bans, or are we in for a Kabuki theater of consent in which civil society said what it wanted, the legislative body listened, rights groups celebrated the proposed bans… And the executives will next bulldoze the will of the people in order to give the security apparatus and industry what they want, because this is how power works?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are practical ones about managing finite resources under uncertainty. I can’t answer them.

This post features a brief civics lesson, because I had to figure out what the hell was going on here, and you might as well, too. (H/t Caterina Rodelli at Access Now and EDRi’s Activist Guide to the Brussels Maze; all mistakes remain mine alone.) Then, it predicts which bans will live (social scoring, emotion-recognition) and die (real-time biometrics and predictive policing in public spaces), and why. It then pulls back and asks, given the stakes, where scientists and activists should spend our limited resources. It makes a strategic and first principle case for defending the (relatively defensible) emotion-detection AI ban, instead of sinking resources into defending the (probably doomed) bans on real-time biometrics and predictive policing in public spaces.

However, in theory, we don’t have to choose! Because making the case well against one of these forms of mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems implies making the case well against all of them. It’s all probability theory, all the time; and it’s worth spelling out again and again, because apparently it’s not very well understood. Case in point, I don’t see anyone linking Chat Control with the AI Act bans on other forms of mass security screening for low-prevalence problems. But it’s the same math. I’ll explain this in a future post.

Brussels Sausage: How European Law Gets Made

When someone does a Schoolhouse Rock (vintage American civics cartoon) about how a European bill becomes a law, it’s going to feature a set of three siblings beating each other over the head with the draft. First, the big kid, who’s supposed to be neutral (whatever that means) — the European Commission — normally introduces draft legislation, as they did the AI Act in April. This is the version they introduced, which I printed out recently to figure out what was going on. It didn’t ban much at all. Yawn.

But many outlets seemed to report the AI Act contained different content! Many outlets did report the AI Act contained different content. Because there is more than one version of the bill. Kai Zenner, MEP Axel Voss’s Head of Office, has kindly compiled them all here. Don’t look; so many documents. Spare print-outs of the April version make lovely origami paper, and can be shredded to fill throw pillows. With all due respect to my fellow ignorant Americans, I don’t think most U.S. media outlets understood how European law gets made when they were reporting on these drafts? But maybe it’s just me, and at least my home decor is evolving!

Next up, the middle kid, who’s supposed to be most in touch with their feelings (whatever that means) — the European Parliament — then introduces their own version of the same bill. This is what happened with the AI Act in June. This version listened to a huge number of civil society groups that had expressed concerns about AI degrading human rights. It banned more things. Rights groups celebrated. But they know what’s coming…

The baby of the family, who almost always gets his way — the European Council — either accepts what’s on the table, or doesn’t. The Parliament and Council can go back and forth with their own positions twice, with each taking a second look at the bill. If they then still disagree, the bill goes to a Conciliation Committee with representatives from both. If they disagree, the bill dies. If they agree, it goes back to Parliament and Council for a third reading, and a deal or no deal decision.

In this case, the AI Act seems predestined for at least a second Parliamentary reading after the Council carves out the usual security exceptions. So the Council is who needs to be influenced right now, to the extent that heads of state listen to people like external scientists and activists. They might not be particularly open to influence here, since the general sense is that it’s in European monetary interests to pass AI legislation at the EU level to protect the EU Single Market from interference by state-level legislation. So the Parliament will be anxious to agree to something in its second reading. Maybe it will go to a Conciliation Committee and a third reading, with MEPs sticking to their guns out of the sense that AI legislation really matters for the future of humanity (even though the climate crisis is clearly more existential than anything else right now), and the EU sets the ethical standard for the world. But it’s not going beyond that; no one wants to see the EU not adopt some version of the AI Act. The pressure will be on the Parliament early and often to pass the damn bill.

In any event, these three siblings are probably going to be hitting each other over the head with this bill until at least 2024. I’m not on anyone’s speed dial for optimism, but it’s really pretty cool how the Parliament listened to civil society and proposed these bans. It seems like it might be important for scientists and activists to think about how to use the opportunity this presents in order to promote the public interest. Even if the harsh but normal political reality may be that we can’t win (everything), and we may want to think about that in allocating resources.

Predictions

Take a deep breath in. Now breathe slowly out, find your center, and join me in a little grounding exercise: It’s 2023. Climate change threatens life on earth as we know it. Fascism is on the rise, as threat primes right-wing authoritarianism, and threat keeps rising along with resource problems relating to climate change. Corporate and governmental use of energy-intensive tech oppressing subordinate racial, religious, and political groups is likely to continue exacerbating both phenomena in one feedback loop among many wherein the fossil fuel cartel-captured superstructure doesn’t seem to understand its interests in not driving the world off a cliff. Thought leaders like Robert Sapolsky and Sabine Hossenfelder don’t think free will exists, and that would seem to explain things.

Against this backdrop of bleak structural constraint, the Parliament version of the AI Act pushes back against stupid, evil programs in a probably ill-fated attempt to save humanity from itself. This is a bill that would ban police profiling AI in public spaces. That would include systems built by Palantir.

Palantir is a CIA-funded U.S. big data analytics company co-founded by Peter Thiel, best known for its uses in U.S. national security and policing contexts including the U.S. Department of Defense Mission Critical National Security Systems. There’s been some debate about whether we’re still in a unipolar world; but suffice it to say the U.S. still has more satellite intel than the man on the moon, spends more on security than the next 10 countries combined, and Palantir is its nepo-baby. There is not a chance in hell the EU is going to ban Palantir.

But we’re not in hell, we’re on earth, where crazy things do sometimes happen! So let’s give this outcome a 1-5% chance. It’s non-zero, and that’s practically, hugely significant.

Most likely, the same thing that always happens is going to happen here: The big kid (Commission) suggests an outing. The middle kid (Parliament) counters with a different proposal. The baby (Council) cries that he wants to feel safe, and everybody goes to comfort him and do what he wants.

Or, in the less warm and fuzzy iteration, we’re talking about the public interest in terms of science and human rights. Someone shoots in the air, yells “national security!” and everyone puts up their hands. “Fear is the mind-killer”; security exemptions are the heist.

But the optics matter. The AI Act must contain some red lines to defend against accusations of ethical whitewashing, like those lobbed by Thomas Metzinger. Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz philosophy professor, consciousness expert, and a member from 2018-2020 of the European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, Metzinger criticized the Commission’s “Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI” as prioritizing market over ethical concerns. The Commission’s version of the AI Act continued this ignoble tradition. But it seems civil society groups agreed en masse with Metzinger, and responded to his call to take the discussion back from industry, in their successful pressure on Parliament to craft a new version of the bill with a number of meaningful red lines.

It seems to me that the ban on social scoring will stay (differentiating Europe sharply from the UK), the bans on real-time biometrics and predictive policing will die (after Parliament fights Council and loses once, at most twice), migrants won’t catch any breaks, and emotion-recognition AI could go either way. This is just me reading the room without any particular skill at that or inside information. There’s just been enough backlash on the Continent against social scoring and risk assessment-type systems (more on this in a future post) to at least call that mix of ban and legal regime on these types of programs plausible; whereas the security community wants more Palantir, not less, and it will likely effectively lobby the Council for what it wants. By contrast, there is no well-established emotion-recognition industry with deep and broad governmental ties the way the polygraph (“lie detection”) industry has them in the U.S.; educated Europeans generally laugh at these technologies, because they know they’re bullshit.

If these predictions are mostly true, then it might make sense for scientists and activists to invest some resources in celebrating the proposed emotion-recognition AI ban, and explaining what it means, and why it matters. If this is false, you got what you paid for. But is there really a forced choice about which bans to defend? Could “going broad” to emphasize the implications of probability theory across mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems actually work to defend more proposed bans on an empirical, security-oriented basis? And why does it matter?

Payoffs

Predictions are just best guesses, and mine could be wrong. So what if I’m wrong? The stakes are pretty high here — to the extent that the AI Act turns out to be enforceable. Enforceability was the big problem with the last global game-changing EU tech legislation, the GDPR, or General Data Protection Regulation. Bracketing that, if it’s remotely possible for the EU to actually ban real-time biometrics and predictive policing AI — and the Parliament has taken a meaningful step in that direction — we should fight like hell for that world. From a security standpoint alone, these bans have the potential to limit state abuses of power that undermine security. They do this while also reducing security forces’ growing carbon footprint at a time when that cost of these programs remains invisible, yet drives ongoing global disasters; AI’s not coming with a transparent carbon pricetag, but that doesn’t mean we’re not paying one. These bans also protect fundamental human rights that underpin all civil liberties and the workings of free societies.

In other words, banning Palantir and the rest of a bunch of stupid, evil programs from most of the Continent is on the table. I don’t usually do this, but… Maybe we should consider optimism? Maybe scientists and activists should be busy raising awareness that this is possible, and explaining why it matters?

Or maybe that’s silly! Don’t ask me, I don’t know. I just know what it would be called in risk assessment: Getting Palantir banned from Europe, like it would be if the Parliament version of the AI Act passed, is a low-probability, high-impact event, or a dark horse. Like the fall of the Soviet Union, the stock market crash of 1929, or the U.S. housing market collapse of 2007-2008. The thing about dark horses is, they’re often rare because they haven’t happened in a while, and the fact that they haven’t happened in a while is actually a clue that maybe some regression to the mean, some market correction, or some karmic a$$-whooping (technically speaking) is due. People tend to under-weight such events’ probability because they’re not within our experience, and experience or availability heuristics work well to make a lot of good decisions. Except when dark horses come into play.

This is a bleak time in human history. People who are concerned about this sort of thing are used to scoop after scoop about illegal mass surveillance and other privacy abuses, hotspot policing and other sciencey-seeming but deeply unscientific police practices, and preventable humanitarian tragedies like tens of thousands of drowned refugees at the doorstep of Fortress Europe while we wait for climate breakdown to drive m(b)illions more to migrate or die. Could it be that we’re due a big regulatory win when it comes to tech that can affect all areas of our lives (and sometimes whether people live or die)?

It’s possible that it’s possible, is what I’m saying. But if banning these technologies is in reality impossible, then we should use our limited resources to fight for the emotion-recognition AI ban that’s next up. Otherwise, we stand to lose more than is necessary. A lot more.

How important is the emotion-recognition ban we stand to lose if we waste resources fighting a potentially losing battle to keep the ban on real-time biometrics and predictive policing? And how feasible is it to use the same argument(s) to fight them all at once?

Emotion-Recognition AI

There is no psychic X-ray that can see inside your head, psyche, or body to reveal your internal state — thought, emotion, the experience of pain, and other parts of subjectivity are, well, subjective. Bad science pretends otherwise, but it is bad. Even if there were a highly accurate lie or emotion detector in the lab, it’s not clear that it would be possible to validate its accuracy in the real world. So we’re not likely to find the Holy Grail of seeing inside people’s hearts and minds, and should stop expending resources trying until we figure out a way around the validation problem that has always kept these sorts of things firmly in the realm of pseudoscience. For this and other reasons, I’ve written about why programs that ignore this problem, like bullshit AI lie detector iBorderCtrl, are shams.

It would be worse if they weren’t. Psychic X-rays, if they existed, would undermine cognitive liberty — the freedom of internal state that logically precedes all other civil liberties. Cognitive liberty isn’t explicitly recognized under existing legal regimes, but could be thought of as part of human dignity as included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, and Grundgesetz, Article 1 all-around.

So it would make sense to ban these technologies. Leading European digital rights orgs made a case for banning emotion recognition AI, and outlined how to do it, in this excellent May 2022 white paper. The Parliament listened.

Defending the proposed Parliamentary AI Act ban on emotion-recognition AI is arguably an important first step in constructing an ethical and legal regime that recognizes and protects cognitive liberty, so liberal democratic societies can keep having civil liberties. The GDPR already bans algorithmic decision-making, and various other laws already ban profiling (e.g., equality before the law in Art. 7 UDHR, Art. 2 Treaty on EU, Art. 3 Grundgesetz; non-discrimination in Art. 7 UDHR, Art. 21 Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU). What’s missing from the discussion is a possible ban on the larger class of programs of which emotion-recognition AI is one small part…

Tip, Meet Iceberg

Using emotion-recognition AI on entire populations — like turning iBorderCtrl on non-Europeans crossing non-Schengen borders — in an effort to identify rare baddies is one instance of a much larger family of programs: Mass screenings for low-prevalence problems, aka mass surveillance. Usually, digital rights activists use the term “mass surveillance” to refer specifically to dragnet telecom surveillance, à la NSA programs such as Upstream. But this term means different things to different people.

Public health experts might use the same term to refer to repeatedly measuring wastewater for signs of disease and drugs to infer population-level illness and behavior patterns. Statisticians might use it to refer to screening entire populations for rare problems, which is something closer to the public health meaning of the term, but that also encompasses security screenings like, and ordinary police programs like New York City’s “stop and frisk.”

The purpose of giving such disparate programs an umbrella term is to highlight the fact that they share the same problem structure in probability theory. I prefer to use the term “mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems,” because it highlights an operative contextual distinction between security and other realms like, say, medicine. In security, a positive screening on one test often wrongly implicates a lot of innocents without ever allowing them to definitively clear their names.

Imagine, for example, a DNA match implicates someone you know in a heinous crime. You might think that’s fairly definitive proof. (Until very recently, I did.) But, in reality:

A DNA analysis, by itself, can establish only that someone could be the source of a genetic evidentiary sample (p. 148)… The inherent uncertainty depends on the different population frequencies of different DNA profiles and the possibility of laboratory error, although anomalies such as police misconduct or planted evidence are also possible (p. 160)… Since the chance of a coincidental DNA match increases with the number of samples analyzed, the population frequency of the DNA profile should be multiplied by the size of the databank to reflect the new chance of a random match. But that does not affect the chance of a laboratory error or its relation to the new chance of a coincidental match. The chance of a laboratory error is usually greater than the chance of a coincidental match, but it could be the other way around given a databank large enough (p. 162). — “Communicating Statistical DNA Evidence,” Samuel Lindsey, Ralph Hertwig, Gerd Gigerenzer, Jurimetrics, 43, 147-163 (2003).

So even when it comes to DNA, mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems don’t mean what most people think they mean. The illusion is that they offer a great security gain for a negligible liberty loss, so of course we should take the deal as a society. But that’s a false opposition masking substantial losses across domains, in part because uncertainty and error plague the outcomes. There’s no secondary screening on par with DNA that can then clear falsely implicated innocents. Those innocents may then suffer the trauma of investigation and possibly prosecution, along with social and professional damage.

By contrast, in medicine, a positive screening can very often be followed up with a secondary screening test (or five) to better determine what’s going on. This isn’t true in every case, and it tends to be truer in some realms (e.g., blood disorders) than others (e.g., autoimmune disorders). Returning to the tech realm, if a neonatal jaundice screening algorithm flags a newborn as possibly having jaundice, you can do a blood test for bilirubin to see if it’s right. But if a predictive policing or individualized risk assessment algorithm flags a neighborhood as a hotspot or a person as a security risk, that can create a feedback loop by causing more policing observing more crime. There is no blood test that lets us get at “ground truth” in security contexts like there is in health, and selection bias plagues efforts to approximate one.

False positives of mass screenings also have different implications across realms — more testing and treatment in health, versus more interrogation and policing of inequalities in security. Sorting people into classes to give the ones who need it a service (healthcare) is qualitatively different from sorting people into classes to give the ones who deserve it punishment or exclusion.

So it might be feasible to use the same resources and arguments to fight to keep the proposed AI Act bans on different mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems, although we would want to be sure to distinguish the contexts (e.g., security, not health) on empirical and first principle grounds. But the best way to do that might be to situate the argument in the context of the emotion-recognition AI ban, and gesture at generalizability. Because that ban is probably the least politically vulnerable, and arguably the most important to defending human rights.