Abortion as a Screening Problem

The structure implies type I and type II errors, so why not count the bodies?

Life or death. That’s what abortion is about to both sides — they just mean different things. Pro-choice activists typically frame it in terms of elective abortion access promoting women’s health, while often denying evidence suggesting it may net harm women’s health instead. Meanwhile, pro-life activists typically frame it in terms of protecting unborn life, overlooking the possible harm that abortion restrictions can impose on women, including in cases where miscarriage or pregnancy complications endanger women’s lives. Both camps emphasize moral urgency and certainty, along with the sui generis nature of the problem: two lives depending on one body, with existential interests that may conflict.

But what if abortion is just another screening problem? After all, it’s a binary decision (abort or not) with a binary outcome (baby later or no baby later), if you throw out some cases (e.g., failed medical abortions and stillbirths).

In fact, what if it’s just another mass preventive intervention for a low-prevalence problem? Mass — according to the WHO, most unintended pregnancies globally end in abortion (though we have no way of knowing if this is true; if true, it would be historically anomalous and have massive sociopolitical implications). Preventive intervention — it typically prevents a birth. Low-prevalence problem — the life-or-death problems it prevents are rare (e.g., birth of a baby with severe congenital defects, or death of the mother from miscarriage, pregnancy, or birth complications).

The usual two types of error

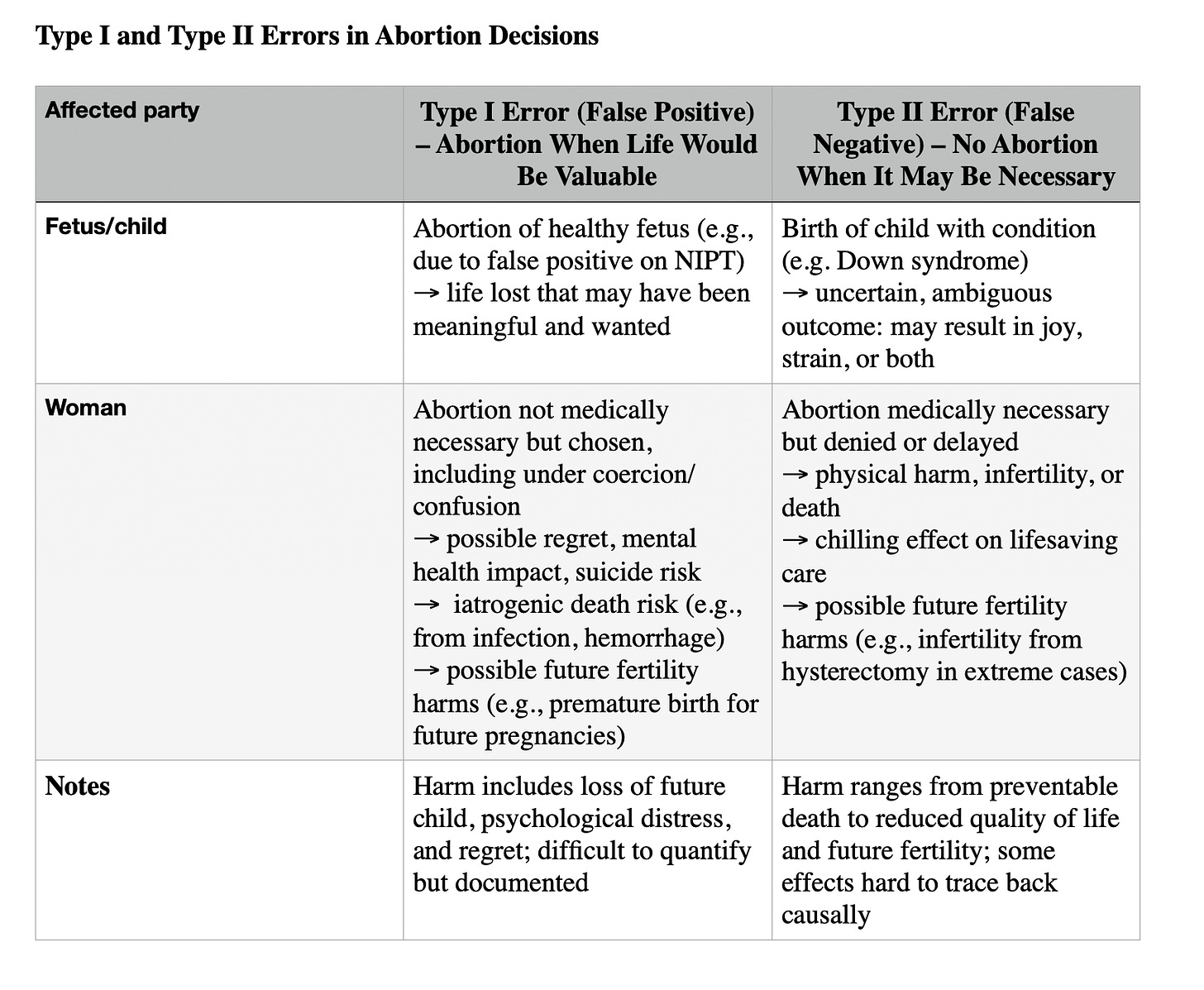

This structure implies certain characteristics. One is that two types of mistakes occur: type I errors (false positives) and type II errors (false negatives).

In this context, that means that healthy babies can be mistakenly aborted after being flagged (e.g.) as having Down’s syndrome by non-invasive prenatal tests. (This looks to be rare, on the order of 1/1000; see the Harding Center NIPT Fact Box and my critique of it. But we don’t know how often it happens on the basis of much less accurate first-trimester ultrasound screening alone.)

Conversely, fetuses with congenital anomalies can be missed in such screenings, resulting in births.

It also means that women may undergo abortion under coercion, pressure, or uncertainty — making a binary life decision that ends a potential future. This may cause or contribute to the associated ~2x increased possible suicide risk.

Conversely, women denied abortion may then go on to have babies they love, or babies they put up for adoption, or babies they struggle to bond with but nonetheless raise. They may also themselves die from miscarriage, pregnancy, birth, or postpartum complications. So babies and women both have existential skin in the game.

Unknown net effects

Another component of this problem structure is that we don’t know the net effects. We can estimate them incorporating a lot of unknowns. But those are still estimates containing a lot of uncertainty. As in most cases, we would need randomized trial data to know the net effects of the intervention of abortion access or restriction.

And we’re not going to get it here, because it would be ethically and practically impossible to run a randomized trial on this.

So what if, instead of claiming certainty (net loss of life on one side or the other) and arguing for a restrictive or liberal abortion policy regime on that basis, we asked: What’s the balance of possible harms? And what does policy owe society when the data are uncertain?

Abortion as screening

This post argues that the epistemic structure of the problem as a probabilistic screening context with uncertain outcomes and asymmetric harms is under-recognized. If we care about net lives, we should attempt to estimate the net effects of different abortion access regimes in terms of type I and type II errors for women and children. If that type of analysis doesn’t (can’t possibly) credibly yield a dichotomous answer, then the better policy question becomes: which kind of errors are we more willing to tolerate in the aggregate?

In this context, abortion policy is best viewed as a societal bet on which type of error we’d rather risk. It would help to know more about the specific numbers that should go in these boxes. Or would it?

The complexity of calculating net harm for women and children might not be reducible to this kind of a model. For instance, there are a number of value-laden interpretive choices that go into what we should consider a potentially existential harm; pro-choice analysts might argue that costs to women of unwanted pregnancies/births can have eventual life-or-death effects, or that their quality of life costs should be figured into net analyses even if they don’t.

If we could agree we care about net lives, then it might be worth filling in the boxes. But maybe we can’t agree on that.

So scientists would do well to be more accepting and transparent of the fact that we don’t know the net effect of abortion policy regimes. Going forward, we should strive for better evidence to assess that, and more open reasoning based on value prioritization that science can neither give us nor justify.

Nonetheless, both sides tend to claim the mantle of scientific neutrality. This claim is unconvincing, and both sides should drop the pretense. In the absence of strong net-effects evidence on whether abortion saves or costs lives*, both sides should instead name the values driving their scientific analyses, policy positions, and personal decisions. It might help reduce bias by removing it from the language of science in which it’s often inappropriately clothed. It would certainly be more transparent.

*unless it’s possible to just do this analysis well, and confirmation bias (already believing the question is settled) rather than futility is the reason that no one has apparently done it.