Book Review: Fed Is Best

A vital infant feeding primer on harm prevention — with space to deepen evidentiary rigor and broaden the challenge to illegitimate authority

In The Rogue Methodologist Ninjas’ Handbook of Punk Science (forthcoming from White Coat, Black Heart Press, 2027), the infant feeding reform chapter stands out for its poignancy, global significance, and delicate balancing. On one hand, the book’s dozens of featured case studies spanning diverse issue areas all critique unscientific science, replacing instructive, top-down science communication with fairer and more transparent evidentiary standards — by giving people complex, ambiguous evidence and the tools to evaluate it themselves, instead of telling them what to do. On the other hand, people — especially exhausted new parents with vulnerable newborns — want to be told how to safely feed their babies.

Balancing these demands required confronting uncomfortable unknowns: How do we reform infant feeding norms in low- and middle-income countries as the climate emergency accelerates? In what subgroups could even safely supplemented breastfeeding cause harm? Which newborns need extra nutritional support from birth, and what’s the best way to provide it?

First, the authors burned down the old house of “Breast Is Best.” Then, they rebuilt a safer shelter, only to burn it down and rebuild again — committed to avoiding confirmation bias and methodological missteps (as much as humanly possible). Eventually, in their ongoing quest for truth and health, infant feeding reformers didn’t just address a broken system; they joined the larger fight for better science.

Honey, I Starved the Kid — 2020

“I like tiny tits,” a lover once smiled at me. “They’re perfect,” a midwife encouraged me when I worried I might not be able to breastfeed, since my breasts hadn’t grown much during pregnancy.

They weren’t: they made barely any milk, no matter what I did. But lactation failure is apparently considered by most healthcare professionals — like the five midwives, four gynecologists, and two lactation consultants I consulted — to be so rare as to be nonexistent. So the professionals dismissed my breastfeeding insufficiency as impossible and, for a time, I believed them. That’s how dangerously wrong infant feeding guidelines combined with bad medical advice — and my own abject lack of common sense — to accidentally endanger my newborn son. If it hadn’t been for a panicked pediatrician’s late-night phone call after reviewing his chart (after having missed many earlier signs) — commanding us to wake up the baby and feed him formula every three hours round the clock — he might not be alive today.

My stupidity was rewarded with biological leniency for reasons I cannot discern. Given how little milk I was making when I finally borrowed a pump to measure, against my midwife’s protestations that it wouldn’t produce an accurate measurement — a fraction of a bottle in a day… And how long the problem went undiagnosed before we started supplementing him with formula — over a month… I do not understand how my son is alive.

Maybe it was because I wouldn’t put him down to go to the bathroom, interpreting “nursing on-demand” in the most literal way possible: he demanded constantly (seeing as how he was starving). So I nursed constantly, not knowing that wasn’t normal. After all, hadn’t I seen pictures of women in the Kalahari Desert doing that? The midwife and my husband chastised me for being overly attached, recommending that I put him down “to organize my closet” or go for a walk alone. But I was listening to my child, or trying.

Maybe it’s because various distributions have long tails, and he rode his luck (and my huge pregnancy appetite) onto one. Born in the intermediate weight percentiles, our breastfeeding misadventure took him down to the low single digits — a repositioning from which he has yet to fully recover.

Whatever the reason, today, my son is a healthy, joyful four-year-old whose self-expression is so advanced that, when people comment on it, his father has taught him to quip: “it’s called ‘verbal development.’ ” His visual acuity and fine motor skills were so detail-oriented that, when he was under a year old, I had to have a mole on my collarbone removed because he wouldn’t stop poking at it. The only signs of lasting impairment so far seem to be not caring when someone calls his name if he’s busy (which he gets from his father), and not caring if he’s driving people crazy asking too many questions (which he gets from me).

You never know, of course, as a parent — especially as a mom — whether your stupid mistakes have harmed your kids, or how, or by how much. You can’t run the experiment twice — and your body was the early laboratory. Sometimes, you launder away the uncertainty to settle on a narrative frame or issue prioritization that serves you and your child better. This is socially desirable and logically wrong.

My preferred squaring of this circle comes from English pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s concept of “good enough parenting”: better an ordinary, imperfect but nurturing home environment than a professionally designed and implemented one that aspires to perfection based on expert standards. Because the former feels real, and kids (like other people) can tell. And because the world out there won’t be perfect, either. And because, as not Winnicott but a raft of other experts suggest, “the experts” are often wrong.

The Fed Is Best Book: A Direct Challenge to the “Breast Is Best” Status Quo

There’s much to celebrate in the story arc of the modern infant feeding tragedy as I understand it, from my personal experience to the recent publication of Fed Is Best: The Unintended Harms of the ‘Breast Is Best’ Message and How to Find the Right Approach for You and Your Baby, by Fed Is Best Foundation Cofounders Christie del Castillo-Hegyi & B. Jody Segrave-Daly, with Lynnette Hafken. My own experience with accidentally starving my son awakened my scientific curiosity, spurring a collection of peer-reviewed articles and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests that suggest we were not weird anomalies after all. Current infant feeding guidance is myth-based, causes common and preventable harm to newborns, and may substantially increase risks of permanent neurodevelopmental disorders.

Someone should be on the hilltop beating a pot and bellowing to warn the (global) village. Luckily, they are. Born from a grassroots effort to challenge universal infant feeding guidelines promoting “exclusive breastfeeding” — feeding a baby nothing but breastmilk for the first six months — without recognizing its serious risks, this book offers a compelling and much-needed critique of current the infant feeding paradigm.

But it stops short of applying the same rigorous scrutiny to all the evidence it considers and medical practices it promotes. While the authors effectively challenge entrenched norms in infant feeding, extending this critical lens to broader systemic issues — evaluating all evidence to the highest methodological standards and questioning illegitimate authority wherever it intrudes — could strengthen the arguments and deepen their impact.

The purpose of this review is threefold: First, I situate Fed Is Best among other related works, and summarize what I understand as its main point in an effort to make it still more accessible to a wide audience (Ctrl + F “haiku summary”). Then, I offer some criticisms of the reviewed science and other aspects of the work as sometimes unscientific, pointing to bias and error in both the literature and the book’s interpretation of it. Far from being pointed, this type of criticism applies broadly to us all and so finds a mooring in the larger context of the so-called “science crisis.” (Except there is no crisis; only human beings realizing it’s only other stupid humans doing science, and has been all along.) Finally, I explore how some of these flaws could be seen as part of shrewd sociopolitical posturing by the authors, whose primary audience I see as being necessarily a popular rather than academic or clinical one. But I make the case for telling people the truth about uncertainty and complexity anyway — and giving them more tools with which to evaluate evidence and think critically themselves. Even though it’s a lot of work, probably a separate book — or part of a separate handbook going wide.

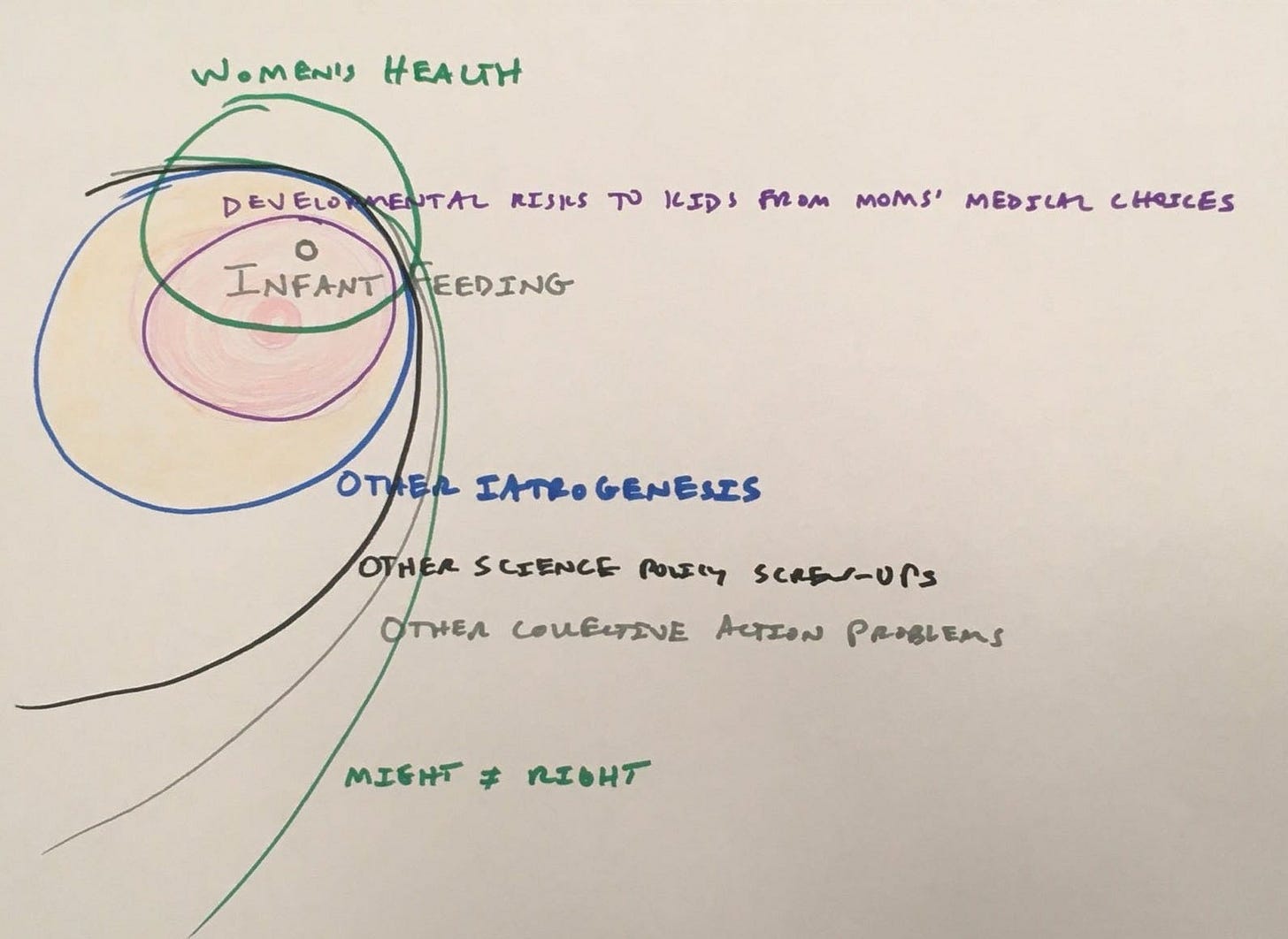

Contextualizing the Debate: Four Levels of Critique

With growing cultural awareness of the role human fallibility plays in institutional practices including across science and medicine — and the effective grassroots advocacy efforts of organizations like the US Fed Is Best and UK Infant Feeding Alliance — more mothers are questioning infant feeding recommendations. When I had undiagnosed lactation failure, I was blindsided, as no one around me confirmed this could happen (quite the opposite). I hung on for a month in guilt and desperation, trying everything to still make it work — before snapping out of it and diving into the (pseudo)science that had led me to that place. In contrast, when a friend had chronic insufficient milk a few years later, she rage-quit breastfeeding in short order, texting me “Fed Up Is Best!”

The Zeitgeist had shifted. Institutions and professionals invested in the old paradigm were digging in their self-interested heels, but the social temperature on infant feeding was changing. You just can’t keep a story like this secret in the age of social media. There are too many women who want to be sure other people’s children don’t suffer like ours did. And we are not going away.

Yet, even with this cultural shift, traditional voices like The (Womanly) Art of Breastfeeding (by La Leche League International), The Breastfeeding Book (by William and Martha Sears), and The Positive Breastfeeding Book (by Amy Brown) remain influential. This is not just for reasons of inertia. Originally, in the late 1970s, “Breast Is Best” had the anti-establishment edge of telling women to trust their bodies and do it themselves instead of relying on (then predominantly male) medical experts and Big Formula to feed their babies.

In an era of ongoing gender conflict and corporate corruption, that message still resonates. Mistrust abounds, and it can be weaponized to make people mistrust any group or perspective. The Boob Boosters — books that issue a Level 1 critique of other infant feeding norms — weaponize women’s mistrust of authority to promote what has by now long since become the new status quo.

So there’s a market for critiques that work at this level, talking to parents about how they’re going to feed their babies, and even promoting breastfeeding to some extent. Where the competition presents breastfeeding as the universal, optimal ideal, Fed Is Best challenges that ideology with a value prioritization in which preventing harm from common breastfeeding insufficiencies — and, even when that’s not an issue, individual choice — matter more than maximizing breastfeeding rates.

On strict cost-benefit terms, Fed Is Best blows the competition at this level out of the water. Standard breastfeeding books rarely if ever mention possible risks of the exclusive breastfeeding paradigm, much less problems in the evidence linking breastfeeding with benefits. So replacing them with Fed Is Best as the new infant feeding Bible would improve infant safety by preventing a lot of harm.

One level up, there are critical, subject area-focused works like Emily Oster’s Cribsheet, Suzanne Barston’s Bottled Up, Joan Wolf’s Is Breast Best? and Courtney Jung’s Lactivism. In a way, these are higher-level critiques — they follow more academic norms (e.g., in citation practices) and engage more with other conversations (e.g., Wolf brings in some lit on informational cascade).

But actually, the Skeptics — books that issue a Level 2 critique of the now-dominant “Breast Is Best” paradigm — are not as skeptical on the whole as Fed Is Best. Where Oster and Jung give the (pseudo)scientific literature on breastfeeding too much credit (e.g., missing the shoddy causal logic in PROBIT), del Castillo-Hegyi et al present a stronger case for confronting its shaky foundations.

That said, it seems in places that the Fed Is Best authors’ opinions may have diverged, with one voice in the book repeatedly presuming breastfeeding benefits that another voice acknowledges are insufficiently supported by the scientific evidence. Moreover, the confrontation with bad science is limited to critiquing “Breast Is Best,” where it could be extended to science more broadly as a cultural institution (as Wolf does).

Zooming out to look at the bigger picture on one axis, another set of related critiques examine how gender bias can lead science and medicine astray, especially in women’s health. Gendered Lens books issue a Level 3 critique of specific women’s health misadventures as instantiations of a broader problem of misogyny in medicine. Recent examples include Invisible Women by Caroline Criado Perez (critiqued here by statistician Stephen Senn), Unwell Women by Elinor Cleghorn, Rebel Bodies by Sarah Graham, and Doing Harm by Maya Dusenbery. There are strains of this sort of critique in Fed Is Best, but it’s not in this flock.

On one hand, there’s a possible criticism in that observation; the book could better recognize the good company in which the modern infant feeding debacle finds itself as one case study among many in this issue area. On the other hand, most books of this type fall short of the highest methodological standards. They could be done well as science criticism; but usually settle for doing social criticism instead. This limits their audiences to people who already agree with the social criticism. Fed Is Best did not fall into that trap.

But, there is still a bigger picture. Some books point out There’s Something Rotten in the State of Medicine/Science. These broader Level 4 critiques, like Richard Harris’s Rigor Mortis and Seamus O’Mahony’s Can Medicine Be Cured? tackle deep-rooted structural flaws in research and healthcare systems, calling for greater transparency, reform combatting perverse incentives, and integrity. Frank Furedi’s Paranoid Parenting: Why ignoring the experts may be best for your child could be seen as an earlier critique on this level. Critiques of this type are all (at best) about how perspective perverts professionals because we are stupid, with pervasive cognitive bias, methodological mistakes, and perverse incentives distorting intent into income.

This is the level where Fed Is Best does not fit, and could have been a better book if it had (or, perhaps, will still become a better handbook chapter when it does). While these four groupings of critiques tend to get more radical as they extend to situate their problems of interest as parts of bigger pictures, Fed Is Best consistently proposes institutionalist solutions to what might be seen as institutional problems.

It is as if the authors are committed institutionalists who have had a religious experience (the exogenous shock of witnessing massive preventable harm from the “Breast Is Best” paradigm), converted (constructing an alternative “Fed Is Best” paradigm), and yet in doing so, held onto their previous beliefs (breastfeeding is beautiful and good, institutions are to be trusted and relied upon for help, authority is legitimate). Such syncretism is typical at both cultural and psychosocial levels. But the rabbit hole goes deeper.

There remains a place for a book that says so. It might more convincingly reclaim the anti-establishment edge from the breastfeeding mafia by incorporating a broader critique of the unscientific nature of much of science. But then we would have to confront the fact of our powerlessness to stop relying ultimately on trust.

We are too busy to look everything up all the time, and anyway the evidence often doesn’t offer a clear, actionable answer. So we need to be constantly playing defense against the myth-based social practices that pervade medicine and science. But we can’t.

We could, however, learn better skills for finding the truth signal in the propaganda noise — especially when we’re scared, tired, and time-pressured — in short, at our most vulnerable. That’s when authoritarian impulses and other forms of stupidity take over, and we’re more likely to just do what we’re told. But it’s also exactly when we most need to be punks — and think things through, instead.

For this, we need a punk science handbook. One that goes beyond debunking specific myths, or decrying the existence of bias, error, interest, and other forms of perspective in some niche context (yes, we are stupid humans; yes, they are really pervasive features of our work, everywhere we go). One that explores how to sniff out spin in science and science communication. And what to do with the ambiguity and complexity that usually characterize the imperfect evidence we have.

That is what this book does not do, that should be done. This warrants a deeper look in a future post.

However, Fed Is Best fills a different, vitally important need in the (mis)information ecosystem. It is enough to take on the WHO, the UN, most world governments and relevant medical associations, and a vast cultural swamp of asinine, unsupported but devoutly preached breastfeeding myths. It is enough to try to save other people’s babies from the fate (preventable death or permanent brain damage) that yours and others’ have met. It’s a capital-g Good battle that should have already been won, but that will likely continue unfolding over many more years to come — although the evidence has long supported a harm prevention model of infant feeding, and the stakes could not be higher. Here’s the crux of the matter…

Haiku Summary: Feeding Basics for Newborns

feed the damn baby.

15 mL milk*.

again as needed.

*Age-appropriate infant milk, probably formula. Much infant feeding guidance promotes using donor breastmilk in the absence of adequate “mother’s own milk.” It generally fails to mention that this is usually impossible — donor breastmilk being accessible only through limited hospital supplies, usually slated for sick premies. Moreover, the recent MILK trial found that premies may actually have a survival advantage on formula. No surprise there (unless you believe in magic boob juice) — formula has more calories per gulp and more vitamins, helping tiny babies gain weight faster and avoid nutritional deficiencies that can compromise their as-yet-tenuous immune function. It also avoids the possibility that vitamin supplements added to breastmilk get stuck on the tubing or other means of administration — something that happens (see Measurement error in NICU vitamin supplementation).

Key Takeaways: Infant Feeding Guidance that Puts Infants First

Babies, infant feeding reformers argue, are human. Scientific evidence suggests their stomachs are not magical, contrary to what exclusive breastfeeding proponents often claim — starting at 5-7 mL on day one and growing to 45-60 mL by day seven. Instead, babies are born able to drink the amount of milk they need to maintain their weight — an amount that most mothers cannot produce for at least the first 48 full hours, or until their mature milk comes in.

Current infant feeding guidance teaches parents to unwittingly starve their newborns in this prelacteal period, causing recently normalized weight loss in the mortally risky postpartum period, and risking permanent neurodevelopmental damage or death — for no proven benefit. While this ideology is cloaked in the language of science, it’s based on pseudoscientific bullshit that defies both common sense and humanity. You wouldn’t starve a hungry, crying puppy or kitten; so don’t do it to a newborn.

What does this mean for new parents? Feed your baby. A 15 mL formula supplement after nursing (if you nurse) should prevent common harm from breastfeeding insufficiencies. There is inadequate scientific basis for the smaller supplemental amounts breastfeeding proponents sometimes recommend — and, in fact, they have been associated with preventable hospitalizations in trials (see ELF-TLC FOIA results). Adequate supplementation, in contrast, protects against accidental starvation and the associated host of potential dangers including permanent neurodevelopmental damage or death from starvation complications like jaundice, hypoglycemia, and hypernatremia. Some moms will make enough colostrum and milk for their babies from the start — but they are the exception, not the rule.

There are a lot of unsubstantiated myths about formula-feeding risks; ignore them. Bigger babies need more milk and, like most babies, will tell you when they do. You can try to calculate the right amount based on age, gender, weight, and weight loss. Or you can just listen to your baby and feed 15 mL at a time in response to hunger cues like rooting and fussing — or every three hours round the clock early on and in response to accidental starvation cues like excessive sleepiness and lethargy.

If global infant feeding guidance were replaced overnight, changing from “Breast Is Best” recommendations to feed babies only breastmilk for the first six months, to something else, this is what should replace it. There’s one small problem: supplemental formula-feeding isn’t a feasible global standard under the current international legal regime that forbids companies from donating free or low-cost formula (more on this later); that should change. But it’s feasible in the modern Western world, and would prevent a massive amount of suffering and harm.

This is the book’s main message, and I hope it gets out far and wide — as it already has through the authors’ extensive social media presence, mainstream media engagement, and concerted efforts to do dialogue with committed proponents of the status quo.

Now some places where we see things a little differently…

CRITIQUES AND MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Debunking the Myth of Newborn Stomach Capacity

A widespread myth, promulgated by exclusive breastfeeding ideologues, claims that newborn stomachs are tiny — holding just 5-7 mL on the first day of life — and then grow rapidly: to 22-27 mL by day 3, 45-60 mL by day 7, and 80-150 mL by one month. Conveniently, these volumes roughly match how much milk most mothers produce at each stage. The implication is that, during those early days, when most mothers only produce small amounts of colostrum before mature milk comes in (a process called lactogenesis II), Mom’s limited milk supply perfectly matches baby’s stomach capacity.

Turns out we have ultrasound measurements of term infant stomach volume in utero that challenge this idea — along with studies using aspirate, balloon, and autopsy measurements (p. 40-41). So while exclusive breastfeeding proponents often say formula-feeding in the first days of life stretches the newborn’s tiny stomach, increasing future obesity risk, the evidence doesn’t establish this. Rather, it looks like the myth of tiny newborn stomachs rationalizes starving infants during this critical period — misinforming parents about why their babies are crying and what to do about it.

At the same time, there’s not a lot of evidence here on which to base sweeping claims about anatomy and physiology that may vary quite a bit, a caveat del Castillo-Hegyi et al don’t seem to recognize. Nor should we assume that stomach capacity neatly determines newborn milk consumption during the recovery period immediately after birth, when some weight loss is common also among formula-fed babies, and this is widely assumed to result from a greater need for rest — something the authors do acknowledge.

This raises questions: If underfeeding newborns carries such serious risks and is so common, then why not mitigate those risks with more than just milk in the first days of life? Why not give babies who are too exhausted to eat enough to maintain their body weight, perhaps from especially lengthy or difficult labors — or who are otherwise at heightened risk of neonatal hypoglycemia (e.g., from maternal diabetes), extra nutritional support? Why not, for instance, make premie formula — with more calories per gulp — standard for the first 3-4 days, when many babies (breast and formula-fed alike) lose weight — and then advise switching to the standard, gestational-age appropriate formulation after that, or when it’s clear the baby is eating enough?

This harkens back to numerous prelacteal traditions that involved giving newborns sweet stuff (e.g., sweetened herb water). On one hand, scientific evidence doesn’t establish the benefits and risks of low-tech interventions like this; it doesn’t even establish them for things like oral dextrose gel. The point is not that we have the answer, but that we should ask the question. “Breast is Best” ideologues told people worldwide to stop giving their newborns sweet prelacteal feeds, and now it’s not clear that was actually in babies’ medical interests. So maybe we should back up a bit and ask what is.

Does Upright Feeding Really Prevent Infections?

Del Castillo-Hegyi et al write:

how you position babies while bottle feeding makes a difference in developing ear and respiratory infections. A clinical trial conducted in Israel found that counseling parents who bottle-feed their babies with formula or breast milk to do so with the baby’s head and torso in an upright, 90-degree position dramatically reduced rates of respiratory infections and related conditions. Researchers randomly assigned participating pediatric clinics to the intervention group (counseling on upright positioning) versus control (no counseling)… (p. 279).

There’s a methodological problem here: The referenced study, described in Avital et al’s 2018 Sci Rep article “Feeding young infants with their head in upright position reduces respiratory and ear morbidity,” wasn’t a randomized trial. It cluster-randomized clinics. Two of them.

As leading obesity researcher and evidence-based medicine reformer David B. Allison and colleagues wrote on the reproducibility crisis:

In the course of assembling weekly lists of articles in our field, we began noticing more peer-reviewed articles containing what we call substantial or invalidating errors… After attempting to address more than 25 of these errors with letters to authors or journals, and identifying at least a dozen more, we had to stop — the work took too much of our time… Science relies essentially but complacently on self-correction, yet scientific publishing raises severe disincentives against such correction. — “Reproducibility: A tragedy of errors,” David B. Allison, Andrew W. Brown, Brandon J. George, & Kathryn A. Kaiser, Nature Comment, Feb. 2016.

Avital et al made the first of three common errors Allison et al identified in their reproducibility essay:

Mistaken design or analysis of cluster-randomized trials. In these studies, all participants in a cluster (for example, a cage, school or hospital) are given the same treatment. The number of clusters (not just the number of individuals) must be incorporated into the analysis. Otherwise, results often seem, falsely, to be statistically significant. Increasing the number of individuals within clusters can increase power, but the gains are minute compared with increasing clusters. Designs with only one cluster per treatment are not valid as randomized experiments, regardless of how many individuals are included.

Avital et al made both design and analysis mistakes described here. Their design used only one cluster per treatment, and so was invalid as a randomized experiment. And their analysis didn’t account for the number of clusters.

These methodological mistakes don’t invalidate the possibility that upright feeding prevents infections. Del Castillo-Hegyi et al highlight (p. 280) possible causal mechanisms whereby supine feeding might contribute to infections (i.e., formula entering the middle ear through the Eustachian tubes, or infants breathing milk into the lungs). We don’t know if there is an upright feeding infection prevention effect or not based on Avital et al. There might be — there are plausible causal mechanisms; so it could be a practice change worth making for parents and clinicians alike. There might not be — and it would be unfortunate for the authors to challenge some infant feeding myths (e.g., that you need to take the bottle away from a hungry baby periodically in so-called “paced feeding”) while promoting others.

The scary thing about catching this problem is that this is the first and only study I’ve looked up from this book so far. It could be a fluke. Or it could be a sign of a deeper problem — that maybe the authors interrogated the foundations of the evidence they didn’t like, and didn’t hold the evidence they liked to the same level of scrutiny (confirmation bias). That would be a normal, human problem. We should still try to hold everyone to the same methodological standards.

There are indications that this happened in several other instances, like the discussion of an MRI study showing evidence of brain damage in 94% of healthy term newborns with hypoglycemia symptoms — and finding 65% showed developmental impairment at 18 months (p. 88). Studies like this will tend to suffer from extreme selection effects as well as small sample size problems.

There are also good examples of a larger uncertainty-laundering problem that’s pervasive throughout the book — as it is also throughout the medical and scientific literatures (not to mention the rest of society). So it’s a pervasive problem, but it’s still a problem.

Hypoplasia Screening — Making a Mountain Out of a Molehill?

Fed Is Best addresses breast hypoplasia (aka insufficient glandular tissue), a presumptively rare and untreatable cause of little or no milk production. But the evidence base for hypoplasia is very limited; in fact, we don’t know the incidence, and Jung called it common in her book. Also, diagnosing it wouldn’t meaningfully change the Fed Is Best advice for moms to supplement early, often, and enough. So del Castillo-Hegyi et al’s proposal for universal prenatal screening for hypoplasia raises serious concerns.

As I often lament on this blog, programs that share this program’s mathematical structure — mass screenings for low-prevalence problems — pose massive societal dangers under common conditions of persistent inferential uncertainty (not knowing for sure what to make of results) and secondary screening harms (hurting people trying to sort needles from haystacks). (See, e.g., previous analysis and recent talk.) The maxim of probability theory known as Bayes’ rule implies that false positives (the common) will vastly outnumber true positives (the rare). This risks creating unnecessary anxiety and intervention for many, creating a false sense of security despite missed cases (false negatives), and expending finite resources on mass screenings and their follow-ups that cannot then be used on targeted screenings with better payoffs.

In this context, there’s no rationale for risking these dangers: universal screening for hypoplasia wouldn’t change what new moms should do. The Fed Is Best advice remains the same: supplement after nursing (if you choose to nurse) until it’s clear that breastmilk supply is sufficient, and continue to supplement whenever hunger cues arise, as supply and demand fluctuate. So there’s no benefit to the proposed screening for infant health.

Del Castillo-Hegyi et al also seem to suggest hypoplasia is uniquely untreatable among causal contributors to insufficient milk, with common interventions like triple-feeding (nursing, supplementing, and pumping every three hours) unlikely to work (p. 140-1). But elsewhere, they acknowledge evidence (and lack of evidence) suggesting this kind of lactation consultant support strategy often doesn’t work, anyway.

One could argue there’s a lot of guilt and shame around breastfeeding problems. Maybe the screening is supposed to make some women feel better about not being able to breastfeed? Maybe that would work for some women.

Personally, I think it’s icky for clinicians to pass judgment on whether women’s breasts are “sufficient” for breastfeeding. Doctors shouldn’t be conducting intimate exams to determine if women’s bodies seem good enough based on criteria that do not reflect sufficient evidence or medical consensus. And if they try to, women should tell them to stop.

That’s not to say that we can’t do a better job acknowledging hypoplasia exists, and preparing women who may have it for the likely need to feed their babies mostly formula. One possible alternative intervention: healthcare providers could suggest pregnant women ask their mothers whether they experienced breastfeeding difficulties, as they likely have a genetic component. Having those conversations in the privacy of their homes might be less fraught with power and judgment than undergoing a not-so-evidence-based breast evaluation by a healthcare provider. (Though, of course, YMMV — your mother may vary.)

There’s also some inconsistency in the authors’ descriptions of how the problem should be diagnosed. In one place, they write that some women with small breasts have no breastfeeding problems; but elsewhere, they write that inadequate breast growth during pregnancy (less than a cup size) indicates hypoplasia. It doesn’t help that we don’t know the general population incidence of hypoplasia, the reliability or validity of this proposed cup-size-pregnancy-growth marker, or the proportion of insufficient milk production cases in which hypoplasia plays a role.

But the real kicker is that Del Castillo-Heygi et al acknowledge that while hypoplasia may contribute to chronic low milk supply and is rare, chronic low supply is common (p. 192). If the common problem is low milk supply, and the intervention for it is prelacteal and supplemental feeding, then we don’t need hypoplasia screening for the rare, poorly understood cause of the common problem. Supplemental feeding should be the general recommendation, and it addresses both problems.

But hypoplasia screening is not just a terrible idea because it’s icky, insufficiently evidence-based, and pointless. It would also expend finite resources (like doctor and patient attention) on exams and follow-ups that could be better used elsewhere, thus contributing to preventable harm. The last thing modern Western prenatal care needs is another mass screening for a low-prevalence problem.

There are already so many such screenings that the drum of their routinization and quantification often jeopardize patient-centered care involving needed targeted screenings for common pregnancy ills, like hypothyroidism and iron deficiency. Such targeted screenings, which often include responsive and ongoing monitoring instead of one-off universal testing, can help prevent harm for mothers and babies alike. Here, the proposed hypoplasia screening parallels other prenatal screenings like gestational diabetes — where overdiagnosis is likely the norm, and yet, a diagnosis wouldn’t meaningfully change what you should be doing anyway. So it offers pain for no proven gain and possible net cost.

In sum, while hypoplasia ostensibly causes little or no milk production, there aren’t consensus criteria for diagnosing it — because there is insufficient evidence to support such criteria. Since insufficient milk is a common problem of which hypoplasia is generally thought to be a rare cause, a more practical approach involves supplementing infants as needed. And letting women keep their clothes on, and clinicians conduct more evidence-based and potentially useful tests.

But there is a social aspect to all this, beyond the math (Bayes says don’t do it!) and the logic (resources are finite, put them somewhere useful!). The default healthcare system advice currently is to tell new moms to “try harder” — eat more, drink more, sleep more, relax more, or take risky and ineffective medications. I know, because I was told all these things, and then set about reading and interviewing the experts who had taught the experts all this bullshit.

The dominant assumption is that everyone can breastfeed. This myth harms moms and babies. Del Castillo-Hegyi et al are fighting it, and they ultimately trust experts to join that fight. Or maybe they want to bring them on board. So they are suggesting experts can do something expert-y to help. Do a screening that acknowledges the problem. Systematize it. Pitch in. It does make a certain psychosocial sense to make the reform effort a matter of medical management.

But the sense seems to be that the authors trust in authority, and want the medical system to participate in righting its wrongs. When maybe we should be encouraging people to question that authority more, instead. Imagine trying to overturn other socio-cultural norms about hypoplasia by appealing to the authority of the people classifying it in the first place…

The Banyarwanda, Agro-Pastoralists in what is now Rwanda, used to regard Twa marriage-age girls with undeveloped breasts as “ ‘revealing in themselves the presence of an evil principle or mystic force whose influence is deadly’ ” (La mentalité primitive, Levy-Bruhl, p. 158; see also Pagés 1933 and Mutton 2005, all from the eHRAF). They would gather up these young women, along with black goats and other undesirables, and kill them in order to expel impurity — on the rationale that this would help solve tribal crises like excess rainfall.

The Banyarwanda equated undeveloped breasts with insufficient milk. Grabbing control from the jaws of chaos by imagining a world in which an easily observable physical sign 100% predicted a deadly problem (tiny tits —> lactation failure —> dead baby). Preventing the problem by killing the women, while claiming the ritual power of their murders for the good of the tribe. It was good versus evil, and killing the hypoplastic women could swing the balance.

Neat trick.

We know now that there are sometimes signs like this — signals that really have a 1:1 relationship with outcomes we want to predict. But that, usually. we are stuck in a world of probabilistic cues in which one data point doesn’t tell us everything we need to know — much less make it rain. Our relative — albeit still feeble — scientific and technological mastery has brought us the insight of science as a human enterprise: the knowledge that reality is usually more complex than this, observations more ambiguous, and interpretations more socially and politically moored.

I have said this book represents a capital-g Good battle to protect other people’s children from harm. That is true. But, at the same time, the heart of the evidentiary matter is not good versus evil. It is good enough and still unknown. Feeding the damn baby is good enough. Much of what we would like to know about hypoplasia, insufficient milk, and indeed optimal infant nutrition is still unknown. So just tell people to feed their babies supplemental milk early, often, and enough. And support research into the unknown — or the parts of it you really care about. I just don’t see a reason to go down the hypoplasia rabbit hole at all, and I’m usually right there with Alice.

The Case of the Missing Citations

The book lacks in-text citations, directing readers to a QR code for references instead. This is frustrating for anyone who prefers to verify claims while reading. When I tried to access the references, I was redirected to a website that required creating an account. After logging in, the site still failed to display references and instead promoted a Fed Is Best Infant Feeding Course and other materials. After emailing the authors, I received a link to an unsearchable PDF of citations without hyperlinks. While helpful, it added needless friction to what should have been seamless.

(Anti-)Standardization Posturing and Global Disparities

The authors frame their takeaway message as advocating for each family to find its own “best” infant feeding approach, rejecting one-size-fits-all recommendations. There is merit in this — especially when considering low and middle-income country contexts, where access to formula and clean water may be significant limiting factors. Then, the recognition that near-universal prelacteal feeding is probably best for infant health means the current international legal regime contributes to massive harms and has to go. Considering that the book’s goal is to overturn global infant feeding recommendations, it is perhaps odd that this regime gets only a brief mention (p. 28).

The WHO’s 1981 International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes — “the Code” — effectively prohibits donation of free or low-cost formula, even in hospitals, poverty-stricken areas, conflict zones, and HIV-endemic areas. While HIV-positive mothers in wealthier countries are advised (or even legally required) to formula-feed to reduce transmission risk, NGOs like the UN and WHO promote exclusive breastfeeding in poorer HIV-endemic regions. This double standard is justified in part on the grounds of preventing “spillover effects” that might lower breastfeeding rates overall. This approach sacrifices some babies to protect others, an ethically and empirically flawed calculation.

Ethically, it lets outside experts decide what’s best for countries that have historically had enough of that already. These experts equate infant deaths from diarrheal disease or malnutrition — which they attribute to formula-feeding, when the causal chain could also include common breastfeeding insufficiencies — with deaths from (or lives with) HIV/AIDS. But the people actually affected by these outcomes may not experience them as equivalent.

Empirically, the calculations behind these decisions are nontransparent. This is problematic, because experts have tended to ignore starvation harms from exclusive breastfeeding — harms that could cause massive numbers of deaths in low-income countries. But even if the calculations were based on sound logic and evidence, they would still assume a trolley problem structure where, on one track, some babies will die from breastfeeding insufficiencies; on the other, some will die from formula-feeding; and states and institutions have to pick a track.

Maybe we don’t have to live in this forced-choice world. Either way, it doesn’t make sense to maintain a legal regime (“the Code”) that actively creates it.

Historically, the formula vs. exclusive breastfeeding debate emerged from pro-breastfeeding reformers’ ignorance about common breastfeeding insufficiencies and their mitigation by prelacteal, supplemental, and complementary feeding traditions worldwide. Now, we know that most newborns need more milk in the days after birth than most mothers make, and that mothers need to need rest after giving birth to support their best shot at successful lactation — the most metabolically intensive act of which the human body is (sometimes) capable. There is no legitimate rationale now for restricting formula aid that could prevent potentially lethal starvation complications in the most vulnerable populations in the world.

Some researchers have claimed on the basis of observational findings that exclusive breastfeeding reduces HIV transmission while partial breastfeeding increases it. However, this interpretation assumes breastmilk is protective and formula/alternatives risky — without considering that sicker women may struggle to breastfeed due to the metabolic/health toll of HIV/AIDS and other illnesses that might in turn also jeopardize offspring health and the ability of mothers and other carers to look after them.

This is another version of the same causal story: As with neurodevelopmental and metabolic outcomes, the evidence cannot say whether existing findings show harm associated with breastfeeding that doesn’t go well (and so mothers supplement or switch — after observing accidental harm), or benefit from exclusive breastfeeding.

It’s possible that sicker women might simultaneously need to supplement their hungry babies more, and also be more likely to transmit HIV in their breastmilk. These mothers may also pay a higher price for attempting to breastfeed: AIDS is a wasting disease, and research suggests that breastfeeding may speed maternal wasting. This could translate into harm to babies whose mothers get sicker, sooner. Orphans often suffer not only loss, but also subsequent neglect, abuse, and worse outcomes all-around.

Mothers matter. Where they have the resources to formula-feed, at whole or in part, most do. More women should have that choice.

Power pervades, but the power dynamics in infant feeding policies are particularly stark. Initiatives that promote exclusive breastfeeding as a way to reduce global inequality can end up deepening it, contributing to preventable newborn deaths, disabilities, and malnutrition, particularly in poorer countries where these outcomes may go uncounted. We need to learn from these failures and develop safer, more inclusive feeding policies amid growing global geopolitical instability.

As climate emergency increases health risks from extreme weather, food insecurity, and disease, more mothers and babies will need emergency food aid and medical care including formula. Yet, some NGOs continue to prohibit formula distribution, even during emergencies, and stigmatize women seeking formula as misinformed. This often results in preventable hospitalizations, prompting outcry from Doctors Without Borders. Aid organizations need more formula to supply in crises, but breastfeeding activists lobby for ever more restricted access, instead. Stress and malnutrition may impair or stop lactation, so this conflict risks harming those who need help most.

It’s time for a new legal and policy framework that ensures formula access as a medical necessity. “The Code,” which bans formula donations even in impoverished and crisis-stricken areas, needs to be replaced with a more flexible system that prioritizes infant health over rigid adherence to breastfeeding ideals.

However, formula isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Safe drinking water remains unavailable in much of the world. The shame of 20th century global public health that we couldn’t (or didn’t?) fix that. The shame of the 21st may be its failure to anticipate and mitigate growing water scarcity.

Increasing susceptibility to supply chain disruptions could also exacerbate formula shortages (like the recent U.S. and Australian ones) in the near future — making it crucial to reconsider other infant feeding options, such as shared nursing and wetnursing with infectious disease screening, safe preparation of other animal milks (e.g., adding sugar and water to cow’s milk to make it more similar to breastmilk), and emerging lab-grown breastmilk substitutes like those developed through precision fermentation. Each option carries its own risks, and a diverse infrastructure will be needed to keep the most babies fed safely.

(A sidenote on precision fermentation: it’s not clear it will scale either in the sense of net energy/climate cost savings or in the sense of being able to make a lot of stuff. Yet some environmental activists like George Monbiot have called for the end of dairy production despite its medical necessity in infant feeding, appealing to the promise of precision fermentation. If debunking the breastfeeding myth teaches us anything, it should be to not unnecessarily create single points of failure with high stakes.)

This is not just a problem in low and middle-income countries. Food banks in wealthy, Western countries like the U.S. and the UK also have to stop banning or discouraging formula donations. Social services have to stop penalizing formula-feeding moms (something Jung has taken flak for researching and writing particularly eloquently on). Researchers and doctors should stop discounting or psychologizing the experiences of mothers who report common breastfeeding problems like insufficient milk, and start listening to women’s experiences and hungry babies’ cries. No mother should have to watch her child go hungry because she’s not able to breastfeed and not believed.

Del Castillo-Hegyi et al target the latter two audiences — healthcare professionals and moms — while neglecting to mention these other structural problems stemming from pervasive “Breast Is Best” ideology. This choice has a benefit and a cost: the benefit is that the book stays very focused on its singular message and conveys it clearly, while the cost is that these big structural issues go largely unexamined in the text.

So there’s a lot of unexplored complexity here in favor of repeating the recommendation to supplement infants with 15 mL of supplemental milk to satiation. This seems like a practical harm prevention strategy, particularly in the first few days of life. Whether parents use formula, donor breastmilk, or other safe infant milk, this consistent approach offers a logical rule of thumb: feed (milk) and read (your baby). If it works better at preventing harm/promoting infant health than existing guidelines, it should be widely promoted. If we don’t know enough to know that it would, we should run a trial (or 10). Especially where local variation makes it hard to know how to get even a small group of vulnerable newborns safe, adequate supplementation — much less how to do it at scale.

Overlooking Opportunities for Deeper Reflection

The authors reference mothers who experience profound feelings of worthlessness or even suicidality when they’re unable to provide their babies with the “best” (i.e., exclusive breastfeeding). They say such cases

require immediate medical/psychiatric care. For some parents, simple interventions like changing their breastfeeding schedule to get more sleep can be enough to improve their mental health. For more severe cases, antidepressant or anti-anxiety medications may be needed along with counseling (p. 199).

There’s no entertaining “depression as costly signaling” here. No recognition that the meta-analytical lit on therapy is pretty suspicious (Scott Alexander summarizes it as “it’s hard to study therapies, and the two most common results are ‘all therapies seem pretty okay’ and ‘whatever kind of therapy the person running the study likes is great’ ”). And no acknowledgment of potential iatrogenesis — harm caused by medical intervention — such as the risks associated with forced treatment or the use of psychotropic medications, which are common but, critics and many former patients charge, often ineffective and harmful.

Ironically, the infant feeding and maternity safety reform movements founded on interrogating the evidence base for the kindred “Breast Is Best” and natural childbirth ideologies often fail to interrogate the evidence base for other medical and psychiatric interventions like this. This is part of a failure to situate these reform efforts in their broader sociopolitical context as one point among many in a mosaic of critiquing unscientific or spin science.

We don’t know whether the authors are unaware of this discourse or if they have chosen to omit it. But the absence leaves a loud silence in the discussion — and results in passing on what arguably amounts to misinformation that serves powerful social and political network interests. In other words, in places like this, the book probably unintentionally parrots spin science — the exact opposite of what it’s trying to do.

The Problem with Prioritizing Parental Choice

The book is written in a mainstream voice, and as such, it reflects certain strains of contemporary culture that don’t make sense outside of our particular sociopolitical context. One of these strains is the ideological reification of choice as an unassailable value, framed in a way that overlooks potential conflicts with other core classical liberal values, namely the rights to life and property in the Lockean model.

In the abortion discourse, for instance, the liberty of a woman to choose abortion conflicts with the fetus’s right to life. Pro-choice reasoning typically resolves this conflict by denying fetal personhood — reifying choice. Similarly, in the trans discourse, the individual liberty of a trans person may clash with with the liberty of a (cis) woman seeking access to women-only spaces. Here, the conflict is resolved in left-liberal discourse by denying difference between cis and trans women — again reifying choice instead of recognizing the conflict.

In the infant feeding discourse, there’s similarly an unrecognized conflict between a mom’s right to choose how to feed her child, and the child’s right to be sufficiently nourished — free from hunger and thirst, their medical complications, and certainly free from death or permanent disability from accidental starvation or dehydration. Here, del Castillo-Hegyi et al, like many others, emphasize the primacy of choice without recognizing the potential conflict between parental liberty and the infant’s right to health and survival.

It’s important to highlight this conflict, because exclusive breastfeeding ideology is so pervasive and strong. Combined with choice reification, this creates a dangerous cultural context in which women can choose to breastfeed even when it puts their kids at risk.

It cannot simultaneously be true that parents should be able to choose whatever feeding method they think works best for them, and that one set of infant feeding norms causes common and preventable harm to infants. At some point, by law, either harm prevention takes precedence over individual choice — or it doesn’t, and harm results. What happens when a baby’s right to be properly fed conflicts with a parent’s desire for exclusive breastfeeding, even when formula is medically indicated?

The infant feeding reform movement seems understandably reluctant to engage with this tension, as it cuts to the heart of the cultural emphasis on parental choice. However, as a society, we need to confront the reality that conflicts between liberal values — such as life versus liberty, or different versions of liberty — do exist. At some point, we have to recognize that protecting infants’ rights to life and health may require rethinking the limits of parental choice. Hospitals and healthcare professionals may have to play a legal role in shifting social norms from “Breast Is Best” to “Fed Is Best,” because the reigning ideology has been inculcated firmly enough to make well-intentioned parents starve their babies.

Taking Quantification and Management Too Far?

Fed Is Best promotes quantification and medical management of infant feeding. I am against this, probably at least in part for constitutional reasons. I don’t want to meticulously monitor myself or anyone else for anything. Because I just don’t want to. I could dress it up as an application of Winnicott — supposing that my child can sense if I’m just caring about meeting his needs versus measuring to see if I agree with his hunger cries, and opting to be a genuinely caring carer instead of an obsessive-compulsive. But I don’t know if there’s anything to that beyond spin. In a quantified self world, I’m not into that stuff.

But there is something more interesting than my own ornery nature at work here: A tension runs throughout the book between encouraging parents to listen to their babies (not the “Breast Is Best” experts) and feed them when they’re hungry, and offering ““a helpful hospital log to track your feeding sessions, weight, and bilirubin and glucose levels” (p. 127) — and encouraging them to ask the experts to use this evidence to guide their feeding decisions.

This tension is part of a fairly old, broad cultural push toward quantification, standardization, professionalization, and giving centrally designed experts power over previously personal or community-designated expert domains. (Think Theodore Porter’s The Rise of Statistical Thinking and Trust in Numbers, Seeing Like a State and probably anything else by James Scott, Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen, and a great many articles by Sander Greenland, including most famously his work on statistical significance testing misuse and other common methodological mistakes that can serve powerful interests by privileging preferred narratives under the auspices of apparently objective science.)

The medical literature reflects that it is an ongoing, relevant cultural phenomenon today. For instance, a recent study in Eur J Pediatr advocates for “tailored recommendations” for infant formula intake, adjusted to infants’ weight percentiles, as a means of improving feeding accuracy. The study found that larger infants required significantly more formula than smaller ones, suggesting a need to move beyond one-size-fits-all guidelines and tailor feeding recommendations to individual babies’ growth patterns. (This is consistent with what Castillo-Hegyi et al say about big babies needing more calories to sustain their weight.)

The authors of Fed Is Best seem to both embrace and push back against this cultural trend. On one hand, they advocate for more monitoring, with recommendations like keeping a hospital log to track feeding sessions and lab results (p. 146). On the other, their core advice — supplementing newborns with 15 mL of milk to prevent starvation complications, as often as the baby says to — is simple and responsive. They acknowledge that excessive quantification can be a distraction, especially when the immediate issue is as basic as ensuring a baby is fed. So why complicate it with charts, weight-loss thresholds, and bloodwork?

Their answer is that:

we must prevent feeding complications for every infant. This requires parents and health professionals to recognize and take seriously the signs of feeding problems and take steps to diagnose them through objective means like weighing, blood testing, measuring milk supply and infant intake, and supplementing before unsafe conditions occur. This requires far more monitoring than is commonly offered in most hospitals…(p. 146).

So the goal is 100% harm prevention. For this, more monitoring is not enough by itself, either. Because we have to trust the baby, but verify with evidence that it’s feeding ok; we have to trust the healthcare professionals to monitor, but listen to the baby when our sources disagree on what it needs…

Thus the authors recommend getting bloodwork done before supplementing if you’re concerned your baby may be hungry (p. 156) — unless baby is already showing visible signs of complications. They also recommend consulting healthcare providers if the baby has lost more than 7% of his birth weight or shows signs of persistent hunger after feeding, “as you don’t have the means to diagnose feeding complications at home” (p. 165). But, in the same breath, they note that waiting for clinical intervention can be risky, as signs of feeding complications like hypoglycemia may already indicate potential brain damage.

So the more practical advice — which they also endorse — is simply to supplement when the baby seems hungry and assess based on the baby’s response, rather than waiting for medical tests or validation. Elsewhere they are clear on this, writing:

Supplement your baby for persistent hunger and for any signs of feeding complications, especially if there is any delay in getting an evaluation or lab results. If your baby stops crying with supplementation, then you know what the problem was. You can work on fixing the problem without your baby suffering. — p. 169

It’s common sense: feed the baby, and if the crying stops, you’ve likely solved the problem. So is medical management really necessary here? Why or why not? Are new parents supposed to trust their instincts and listen to their babies, supplementing to satiation — or are they to rely on data points and clinical assessments? Or a balance of the two on a case-by-case basis? In the busy and stressful newborn period, why should parents bother involving experts in how often they feed their baby milk, if the “right” answer is anyway to let the baby decide? Does deference to authority figure into this tension?

My take is that this is a simple matter; it’s just impolitic to say so. Going along with the larger cultural pressures for quantification, while ostensibly intended to prevent harm, adds unnecessary trouble and complexity to a straightforward task: ensuring a baby gets enough to eat by listening to and feeding it. Like the proposed hypoplasia screening, it’s not clear the proposed monitoring net benefits moms and infants, especially in comparison with the authors’ proposed supplementary feeding standard.

We could treat that as an open empirical question if we don’t know — and I think we don’t know based on available evidence. We could also tell parents it’s not clear what level of quantification and medical monitoring net benefits babies. And they could acknowledge that their approach is quantification and medicalization-heavy. This will not appeal to everyone. It’s a cultural orientation more than anything else, in my read. The authors come from healthcare professional backgrounds. They’re comfortable with medical management. They recommend it. Other people from different backgrounds may not be as comfortable with it, and may prefer to take a different approach. One that’s actually no less evidence-based in terms of its effects on infant health.

The Lingering Influence of “Breast Is Best”

“Breastfeeding is a beautiful and healthy way of meeting a newborn’s need for milk, comfort, and close contact while providing immune protection” (p. 74).

There’s a lot to unpack here. “Beautiful” is an aesthetic judgment with moral overtones. It’s subjective and dissonant with acknowledging some decidedly ugly aspects in other passages, e.g., that 80% of breastfeeding moms report nipple pain, or that some mothers have accidentally killed or maimed their children breastfeeding. “Healthy” seems an odd word to describe a faulty natural process that doesn’t meet most newborns’ needs for milk in the first days of life, can contribute to accidental suffocation, and (the authors argue elsewhere) can cause trauma to ordinary moms and permanent damage to kids when it doesn’t work.

Banging the “Breast Is Best” consensus drum on net immune protection is also out of sync with questioning that consensus. In addition to risks of infectious disease transmission, breastfeeding may carry risks of immune miseducation. Research by University of Copenhagen Pediatrics Professor Hans Bisgaard and colleagues suggested that mothers with asthma who breastfed longer seem to have accidentally put their kids at greater risk for eczema, possibly through passing on inflammatory or otherwise dysfunctional immune substances through their milk.

The possible immune health risks of breastfeeding aren’t limited to kids, either. According to Borba et al, moms, too, may risk triggering autoimmune disease activity by breastfeeding, in this case through its elevation of prolactin. (Other mechanisms are also possible, like metabolic stress contributing to wasting in some lupus phenotypes.)

We don’t know what the net immune effects are of breastfeeding for high-risk subgroups. But there’s evidence that breastfeeding does not only confer immune protection. It also carries risks. These risks are not mentioned.

There are also places where formula’s praises could be sung more based on the evidence, but instead that evidence is omitted. For instance, the authors say more milk speeds bilirubin excretion to help treat jaundice (p. 96) — without acknowledging some evidence suggests that formula speeds bilirubin excretion better than breastmilk. (Probably because it has more calories per gulp, and that means more food in —> more poop out, bowel movements being segmental.)

Relatedly, my own analysis suggested that phototherapy risks iatrogenesis, but the discussion of phototherapy treatment for jaundice (p. 98) ignores this possibility along with the corollary that more aggressive formula supplementation has broad harm prevention potential. Instead, the authors set up banked human milk and formula supplementation as presumptively equivalent in reducing jaundice (p. 99), something the evidence does not establish. Some evidence rather suggests formula is better in this context, and it seems possible that this is just not something the authors felt it was socially or politically wise to come out and say.

These are not one-off examples of lingering “Breast Is Best” ideology in Fed Is Best. To pick a few others…

The authors also say “most babies really enjoy nursing” (p. 202). Obviously, this is not a scientific assessment. Most babies probably enjoy getting fed from a bottle, too. It’s probably the milk and snuggles they can get in various ways, no? Or at least, I can’t imagine a randomized trial one could design to assess this question.

Another instance: “there is so much to enjoy about nursing your baby” (p. 204). It seems like plenty of women find breastfeeding painful, inefficient, degrading, and/or unnecessarily risky for their own health (e.g., suffering common problems like mastitis or sleep deprivation) and their kids’ (since you can’t measure what’s coming out, which is what makes it possible to accidentally starve your kid “exclusively breastfeeding” in the first place).

So why promote breastfeeding with some of the same old pseudoscientific/ideological bullshit in a book proposing a new infant feeding paradigm? What gives?

Shortcomings or Strategy?

Many of these criticisms could fit into a sociopolitical reality wherein the authors are or perceive themselves as savvy reformers working to make the world a better place for other people’s children.

No in-text citations? Don’t get distracted by other people’s names and research lineages; we’re here, we have a brand, we have an elevator message, focus and take it away. You’re an academic and you hate that? Whatever. This change isn’t coming from academics anyway.

A clear standardized recommendation being (mis)represented as a contrast with a one-size-fits-all approach? Critics (defenders of the status quo) don’t have one to (counter-)attack if the message is framed as not having one. It’s would be a weird play insofar as it undermines the recommendation’s accessibility though.

The case against “Breast Is Best” can be seen as one battle against spin science among many. But if you say that, it risks resonating with the current connotations of “Do Your Own Research” — now associated in liberal academic and popular discourse with conspiracy theories, misinformation, Russian disinformation, and ironic lack of critical thinking. So don’t go too far critiquing the status quo. Think critically only about infant feeding — and not also, for instance, about the mental health diagnosis and treatment regime implicated when we start talking about the relationship between “Breast Is Best” and postpartum mental illness… It’s sad but true that leading critics of this regime, like evidence-based medicine pioneer Peter Gøtzsche (author of the recent book Is Psychiatry A Crime Against Humanity?), seem now to be situated firmly outside of mainstream discourse — despite, in his case, having led it for many years. So if you want to stay in it (and win it), then maybe ignore the people who question too much for their own good, and nod along to current medical practices and social norms that fall outside the immediate scope of your strategic goals.

No tour of global suffering relating to the current infant feeding regime, with its added complexities (lack of formula access, dirty water, corruption hindering aid efforts, illiteracy, HIV) complicating the recommendation to supplementation to prevent starvation harms? Reform will have to come anyway from the powerful West and trickle down to deal with these complexities, so staying on-message again makes political sense.

No acknowledgment that, in the majority of cases, it will be impossible to know what harm causally resulted from the “Breast Is Best” paradigm? It makes a better story to pick some tragic cases on a pole of the continuum — e.g., Landon Johnson — and use them as human-interest focal points to advance the reformist cause. That’s an extreme (and impolitic) example of the sociopolitical utility of uncertainty-laundering more broadly.

A careful, sometimes apparently incoherent dance between denunciation of the endless promotion of more quantification, measurement, and professional medical supervision/intervention, and promotion of that same quantification? This way, readers can take away what they like (screw this faux-expert meddling, I’m going to listen to my baby; or, screw this presumptuous one-size-fits-all ideology, I’m going to measure everything to minimize risk). This ambiguity leaves room for a broader coalition of reform-minded people who may disagree about the net costs and benefits of these contrasting approaches.

Repetition of some emotive and factual themes from the dominant “Breast Is Best” ideology. There are numerous references to how beautiful breastfeeding is, or how it’s got benefits (which are actually unproven). I read this as (1) different authors putting different spices in the pot at times, and (2) singing along with the choir enough to not get mobbed (dismissed as anti-breastfeeding). The latter is understandable as a political strategy: Martin Luther didn’t make the Protestant Reformation by questioning whether God exists; he kicked off major religious and political reforms (and wars) by making relatively small changes to the old paradigm. Maybe the same principle holds in infant feeding reform? You can’t just come in and say “breastfeeding is really painful for most women, also starves most babies if you don’t supplement them from the first day of life, and has no proven causal benefits — zero.” Although that’s demonstrably true, I don’t get invited to a lot of dinner parties (and when I do, I don’t go). Maybe in order to be effective socially and politically, you have to come in saying “breastfeeding is beautiful and health-giving, we just need to do it a little bit differently.” Then maybe people can hear what you’re saying.

So maybe my criticisms are largely instances where the authors chose their battles, or opted for sociopolitically advantageous framings where there were more complex and intellectually honest (but less useful or wise) ones. Or maybe they are just mistakes, places where the science and logic in the proposed science-based reforms could be more rigorous. I don’t know.

Either way, this book fills an important hole on the prenatal bookshelf for parents who want to be informed about infant feeding in order to be able to do what’s best for their kids — and on the professional one for people whose work deals with new moms and babies.

tl;dr — Infant Feeding Reform: Urgently Needed; Science Reform, Even More So

On one hand, Fed Is Best presents a clear, common-sense articulation for a desperately needed new infant feeding paradigm: Everyone has to eat enough to thrive. But not everyone has had the ill fortune to see current infant feeding guidance do fully preventable harm. Or the good sense and good heart to go about trying to set things right for other people’s children. There’s a deeply humane beauty in this good-faith effort to improve the world in the wake of personal tragedy. (Christie’s exclusively breastfed firstborn son’s story turned out differently from mine.) It’s also legitimately how some people cope, making socially useful meaning of senseless personal suffering. This effort deserves our deepest respect and appreciation.

On the other hand, there is a larger, more radical task here that still needs attending. “Breast is Best” represents a failure of science to be scientific, and of science communication to be critical. But the Fed Is Best authors still put out some unscientific science and even some breastfeeding myths as if they were facts. Along the way, readers don’t learn any tools for assessing the scientific evidence critically themselves, or gain any license (theoretical or practical) for questioning science communication that uncritically parrots what authorities say science says.

So the babies are fed, but the rogue methodologist ninjas are still hungry.

Thank you for this review, I really enjoyed reading it.

I am reading the book myself and also found some of the advice contradictory. For example, performing blood tests on a newborn baby who shows signs of hunger does not make sense when there is a perfectly safe alternative feeding method available (formula), and goes against the precautionary principle that is so important for patient safety (I am a medical doctor myself).

It also strikes me that their chapter for mothers who want to exclusively breastfeed should come with a lot of warnings about the risk of doing so, especially in the first few days of life. Not providing those warnings seems contradictory to the evidence they outline in the first chapter. Your reflections on patient choice as a value are very interesting for this, I couldn’t agree more.

I also inadvertently starved my baby following breast is best advice. Overall this book is refreshing, but could’ve gone further.

Keep up the good work!

Thanks for such an interesting and thought provoking critique!