A Little Learning Is a Dangerous Thing

Recent readings on screening, heuristics, endpoints -- and why frequency trees may be the wrong tool for my risk literacy job

“A Little Learning”

by Alexander PopeA little learning is a dangerous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts;

While from the bounded level of our mind

Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

New distant scenes of endless science rise!

So pleased at first the towering Alps we try,

Mount o’er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

The eternal snows appear already past,

And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

But those attained, we tremble to survey

The growing labours of the lengthened way;

The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes,

Hills peep o’er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

So I thought I knew something about risk literacy, the base rate fallacy, and protecting people from it by teaching them to grok the implications of the universal laws of mathematics. I knew enough to build Rarity Roulette, a free app that lets people simulate the implications of mass screenings for low-prevalence problems. I knew enough to redesign it with frequency trees when the tables didn’t seem to work as well as canonical risk literacy work (Gigerenzer & co.) suggested. And now I know a bit more from these recent readings on screening, heuristics, endpoints, and why frequency trees may be the wrong tool for the job, after all.

Recap: My pilot studies tested whether interactive frequency table and then frequency tree visualizations help people reason about the implications of base rates in mass screenings. Results suggest maybe they help a bit, maybe they hurt a bit, maybe they have no effect. Differential dropout persisted through two pilots and an intermediate redesign: people didn’t like playing with my pretty toy.

What if I built the wrong toy?

Haiku Summaries

Risk literacy

may mean pattern spotting, not

computing the odds.

Informed consent for

popular screenings may be

impossible. Huh.

Gains come from system

design. Individual

reasoning n/a?

tl;dr —

Feufel & Flach = medical education should teach heuristics, not eliminate them — maybe the right goal isn’t Bayesian computation but “perspicacity”

Hofmann = informed consent for screening may be structurally impossible due to cognitive biases including the popularity paradox

Hofmann et al. = overdiagnosis looks different from personal, professional, and population perspectives — POVs that don’t reconcile

Eklund = screen smarter, not harder — e.g., Stockholm3 reduced unnecessary biopsies around 24-39% (95% CI)

Veal et al = Core Outcome Sets show how to systematically ask patients what endpoints actually matter to them — in depression; implications in oncology/screening research?

Markus Feufel & John Flach (2019). “Medical education should teach heuristics rather than train them away.” Medical Education, 53(4), 334-344.

Markus Feufel is a professor of ergonomics at TU Berlin who trained with Gerd Gigerenzer’s group at the Max Planck Institute; John Flach is an emeritus professor of psychology at Wright State who works on ecological approaches to decision-making. Together they make an argument that reframes the problem.

The argument: Traditional medical education treats heuristics as cognitive bugs to be eliminated in favor of logical/probabilistic reasoning. This is backwards. Heuristics are the basis of good clinical decision-making when adapted to domain-specific challenges. The goal shouldn’t be to make clinicians reason like statisticians; it should be to help them make “smarter mistakes rather than dumb ones.”

Key concept: Perspicacity over computation. Don’t train students to compute probabilities correctly (the Bayesian algorithm use dependent variable in Gigerenzer et al and my pilots). Rather, train them to recognize which heuristic fits which situation, and to catch errors early. Tuning pattern recognition processes > teaching algorithms. (This is incidentally a type of task that human beings are classically better at than AI/ML.)

For example, a positive result in a low-prevalence context should cue recognition of rarity, persistent inferential uncertainty, and secondary screening options including associated costs/harms. It should not generate confident acceptance of a positive result as a known true positive.

Feufel & Flach recommend three pedagogical formats: supervised work with real patients (messy, contextually rich), narrative case vignettes (à la Dancing at the River’s Edge?), and simulation with feedback loops. The last one sounds like what I was trying to do with Rarity Roulette, but with a crucial difference — they’re emphasizing learning from feedback and mistakes in teams, with exposure to cost tradeoffs (what does a false positive feel like vs. a miss?). Not teaching people to calculate PPV.

Implication for Rarity Roulette: My survey instrument tested if the tool taught people to compute PPV correctly (frequency trees → Bayesian algorithm use), and how often they got the right answer (accuracy). Feufel might say: maybe the goal isn’t teaching the algorithm or computing the right answer. Maybe it’s building recognition of when base rates matter, experiencing the cost tradeoffs, tuning perspicacity rather than replacing intuition with calculation. The pattern is the puzzle.

The good news: This isn’t actually a problem with the app. It’s a problem with the way I tested if it “works.”

The bad news: I don’t know how to solve this problem. But I suspect it involves doing a lot more talking to people in real life, and a lot less collecting quick and dirty data on the Internet.

The other bad news: On second thought, maybe it also implies a problem with the app. Because showing people narrative vignettes is different from showing them numbers, just as having them work in teams on pattern recognition is different from having them work alone on computation. So maybe the app is like a numerical spine for a storybook that needs a lot more names and faces.

Bjørn Hofmann (2023). “To Consent or Not to Consent to Screening, That Is the Question.” Healthcare, 11(5) 664.

Bjørn Hofmann is a professor of medical ethics at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) and the University of Oslo who has been writing about overdiagnosis and screening ethics for decades. He argues that valid informed consent for screening may be structurally impossible — which is paradoxical, because screening targets healthy people who should be best positioned to consent.

The problem has several layers:

Historical failure. Norwegian mammography screening historically provided inadequate information about harms. (He nagged them, got harm information added; nagged more, got it quantified. But reports it still cites the authors’ own studies rather than independent analyses.)

Cognitive biases undermine consent: Impact bias (overestimating cancer’s devastation), optimism bias (underestimating personal risk of overdiagnosis), anticipated regret (fear of “what if I hadn’t screened”). The impact bias lens especially echoes Karsten Juhl Jørgensen’s point in a recent conversation about how people tend to misconceive cancer as necessarily lethal.

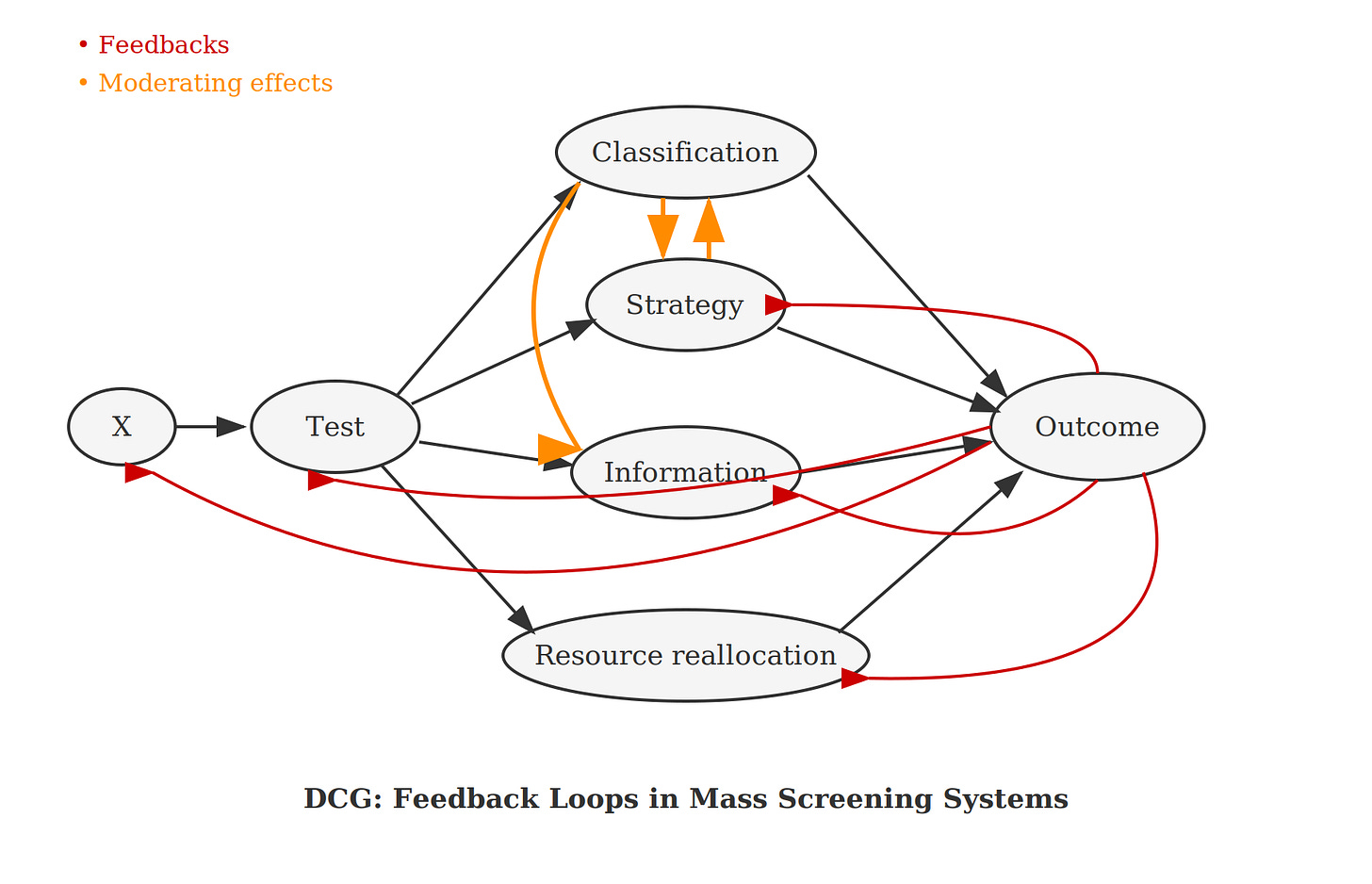

The popularity paradox. People who are overdiagnosed and overtreated believe they were saved — they can’t know they were harmed, so they become screening advocates. This creates a feedback loop that directed cyclic graphs (DCGs) can model: overdiagnosis → perceived benefit → advocacy → expanded screening → more overdiagnosis. (See also Figure 12.4 in Welch et al’s Overdiagnosed.)

Implication: If consent doesn’t work for screening (healthy people, clear tradeoffs), maybe it doesn’t work anywhere.

Connection to Rarity Roulette: This is a cognitive psychology and ethics side of what I’ve been diagramming and trying to intervene on experimentally. Can education overcome these biases? Maybe not, if the biases are too deeply ingrained in the way people think. I’m reminded of the brick wall of confirmation bias; the modal response to being confronted with it, is doubling down. Or maybe the tool simply needs to address the emotional/motivational layer, not just the computational one. So, human interest stories and real-life exercises/work in groups with other humans?

Bjørn Hofmann, Lynette Reid, Stacy Carter, and Wendy Rogers (2021). “Overdiagnosis: One Concept, Three Perspectives, and a Model.” European Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 903-912.

This paper — co-authored including with Stacy Carter and Wendy Rogers from the University of Sydney’s Centre for Values, Ethics and the Law in Medicine — argues overdiagnosis looks different from three vantage points:

Personal perspective: “Would this diagnosis have harmed me if undiscovered?” — fundamentally unknowable for the individual.

Professional perspective: Disease definitions, diagnostic thresholds, clinical criteria — professionals set the boundaries that create overdiagnosis.

Population perspective: Epidemiological estimates of overdiagnosis rates — what policy uses, but individuals can’t apply to themselves.

The problem: These three perspectives don’t reconcile. Population estimates inform individuals, but those estimates depend on professional definitions, which depend on individual suffering. It’s circular.

Key insight: “Population-based estimates of overdiagnosis must be more directly informed by personal need for information.”

Connection to my work: My causal diagramming approach — using directed cyclic graphs to capture feedback loops — could help bridge these levels by showing how professional threshold changes propagate to population outcomes and individual experiences. This is what the policy simulation layer of Rarity Roulette was always supposed to do. Maybe I should just build that part next.

Martin Eklund and the Stockholm 3 Program

Martin Eklund is a professor of epidemiology at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm who exemplifies “screen smarter, not harder.”

Stockholm3 — Blood test combining PSA with additional biomarkers and clinical variables (Lancet Oncology 2015). At the same sensitivity as PSA alone for detecting high-risk prostate cancer, use of the Stockholm3 model could reduce biopsies by around 24-39% (95% CI) and avoid around 35-54% (95% CI) of benign biopsies. Even at the lower bounds, roughly one in four men avoid an unnecessary biopsy and more than a third are spared procedures finding nothing clinically important. (A critic would want to see frequency counts of still unnecessary biopsies that may result in impotence and incontinence, though!)

STHLM3-MRI — Combines Stockholm3 + MRI + targeted biopsies (NEJM 2021). Clinically insignificant cancers were detected in 4% of the experimental group versus 12% of the standard biopsy group, for a difference of 5-11% less (95% CI). Even at the conservative bound, detection of clinically unimportant cancers is cut nearly in half. At the upper bound, it’s cut by more than 90%. Either way, substantially fewer men are diagnosed with cancers that would never have harmed them. (Still: the men who are overdiagnosed, are all getting net harm.)

AI pathology — Deep learning system grading prostate biopsies as well as top urological pathologists (Lancet Oncology 2020, Nature Medicine 2022).

WISDOM trial — US trial (65,000 women) testing risk-based personalized mammography screening.

Core theme: How do we screen smarter, not harder? The answer isn’t just better tests — it’s better combinations of tests, better targeting of who gets screened, and better integration of risk information.

This aligns with what I’ve been arguing about how gains along the test classification pathway in mass screenings for low-prevalence problems don’t necessarily translate to net gains in health/security/whatever. Eklund’s work shows the solution isn’t just improving the classifier — it’s redesigning the system.

Switching domains: Couldn’t this basically be what Palantir et al are all about in security? Nontransparency makes it hard for independent researchers to know, and there is an entrenched debate about whether a similar logic in security contexts would actually work to generate net gains versus just entrenching bias and error, compounding subgroup harms (think policing high-crime minority neighborhoods more because they’re already policed more, either baking in bias from existing data/practices or responding rationally to base rate differences).

Point being, this would parallel Eklund’s lesson: gains come not from better classifiers alone, but from system-level design that targets resources where they matter most. We want investigative resources where they belong (in targeted investigative contexts where prevalence is higher). That stems the tide of possible massive net damages from mass screenings for low-prevalence problems.

In other words: you solve the problem of potential massive net harms from mass screenings for low-prevalence problems, by doing less mass screenings for low-prevalence problems. You change the base rate as much as possible so it’s not as low-prevalence (acting on the rarity dimension). You change the test protocol so it’s not one binary screening but a combination of tests (acting on the persistent inferential uncertainty dimension). And ideally you would also change the secondary screening costs (but the difficulty of minimizing those here is exactly why the problem of overdiagnosis persists in meaningful terms).

Christopher Veal et al. (with Eiko Fried) (2026). “A protocol for the development of a core outcome set for adults with depression.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 191, 112119.

This protocol paper — led by Christopher Veal at INSERM Paris, with senior authors Viet-Thi Tran and Astrid Chevance, ft. Eiko Fried — describes how to systematically ask patients what endpoints actually matter to them. It’s about depression treatment trials, but the methodology transfers.

The problem they’re solving: Trials measure what’s easy (symptom checklists) rather than what patients care about (emotion regulation, mental pain, functioning). Less than a quarter of the 80 outcome domains patients identified as important were actually measured in RCTs. This is the proverbial looking for the lost keys under the lamppost because that’s where the light is.

Their solution: Large-scale preference elicitation — surveying 2000+ people with depression to rank outcome domains, then building consensus on what should be measured at a minimum in all trials.

Why this matters for screening: The same disconnect exists. Cancer research tends to measure what’s easy (five-year survival, cases detected, mortality) rather than what patients may care more about (quality of remaining time, treatment burden, anxiety from surveillance). As a cancer survivor friend put it to me recently, more monitoring may be better for those who know they need to watch, as catching a recurrence earlier could allow for gentler treatment, possibly avoiding chemo. There could be no mortality difference and she’d still rather have more quality time left with her family.

This isn't just anecdote. Zahl, Kalager, and colleagues modeled quality-adjusted life years for Norwegian mammography screening (Zahl PH, Kalager M, Suhrke P, Nord E. (2020). “Quality-of-life effects of screening mammography in Norway.” International Journal of Cancer, 146(8), 2104-2112). Using modern estimates of overdiagnosis (50-75%) and mortality reduction (10%), net QALY was negative — meaning the program causes more quality-of-life harm than benefit. Only under the more optimistic assumptions from 30-40 year old RCTs did net QALY turn positive. So mammography breast cancer screening programs may cause net harm when you count what patients actually care about.

Conclusion: Reorienting Risk Literacy

Where does this leave Rarity Roulette?

The Feufel framing suggests I may have been measuring the wrong thing. If the goal is perspicacity rather than computation, then “did participants use a Bayesian algorithm?” or “how accurate was their calculation?” are wrong questions. Less wrong questions might be: Did they recognize when base rates mattered? Did they hesitate before trusting a positive result in a low-prevalence context? And, conversely, did they jump on investigative opportunities in a high-risk context? In other words, did their confidence and investigative approach calibrate to the actual uncertainty in any given context?

Hofmann’s work suggests the problem may be structural, not informational. If the popularity paradox creates self-reinforcing advocacy for screening, and if the three-perspectives circularity means individuals can’t meaningfully apply population estimates to themselves, then better individual reasoning may not move the needle. People may not be reasoning at all, so helping them reason better may be totally irrelevant to guarding them against potential harms from these programs. The feedback loops I’ve been drawing in DCGs aren’t just methodological curiosities — they’re mechanisms by which well-intentioned screening programs resist correction.

Eklund’s oeuvre suggests looking in a different direction for the action: not in teaching individuals to calculate PPV, but in redesigning who gets screened and with what combination of tests. Don’t try to teach people Bayes’ Rule; teach them relevant pattern recognition instead. Stockholm3 didn’t improve outcomes by making patients better Bayesians. It improved outcomes by changing the system — using risk stratification to route people to different screening pathways.

So maybe Rarity Roulette/risk literacy research in this vein needs to pivot. Three possibilities:

Change the outcome measure. Stop measuring Bayesian algorithm use; start measuring pattern recognition, calibration, and appropriate hesitation. This would require redesigning both intervention and assessment.

Change the target. Instead of teaching individuals to navigate screening decisions, teach clinicians and policymakers to recognize when system-level changes (à la Eklund) would outperform individual-level education.

Add the policy layer. The original vision for Rarity Roulette included a policy simulation component — probably a Rose Diagram — showing how changing thresholds and base rates affect population-level outcomes over time.

The inconclusive pilot results aren’t necessarily a dead end. Among other possibilities, they might be telling me I built the right intuition into the wrong frame. At least, that seems to be a question that I have to ask myself before presenting on my Rarity Roulette research at Charité next month.

I also have to say that I strongly dislike the idea that net gains have to come from system redesign instead of better individual reasoning. It just offends my political philosophical sensibilities. People are autonomous, have choice, and this is foundational to liberal democratic societies. I want it to matter more. I want to fight cognitive bias with individual-level decision aids to empower individuals to make better choices. That was the Rarity Roulette dream!

But wanting something doesn’t make it so. And I guess this is just behavioral economics, right? Structures dominate behaviors not because people are bad or stupid, or even because we’re rational actors (we’re not), but because common bias and error pervade human affairs due to our limited, outdated cognitive-emotional hardware. We’re using every heuristic we can just to get through the day. We evolved to cope with the threat of uncertainty using primarily denial, not to solve inverse probability problems under institutional pressure.

In that context, the lesson may not be that risk literacy is impossible. But rather that we’ve been trying to teach the wrong skill, to the wrong people, at the wrong level.

Pope’s point was that a little learning makes us confident; deeper learning reveals how much we don’t know. The same applies to screening programs. A little knowledge (“early detection saves lives”) creates confident advocates. Deeper knowledge — about base rates, overdiagnosis, the popularity paradox, etc. — reveals uncertainty we’d rather not face. Maybe the real risk literacy challenge isn’t teaching people to calculate the risks. It’s teaching them to sit with not knowing. And that the real decision is (often) not about safety versus danger, but about which risks they’d rather accept.

References

Karin Binder, Stefan Krauss, Ralf Schmidmaier, and Leah Braun. (2021). “Natural frequency trees improve diagnostic efficiency in Bayesian reasoning.” Advances in Health Sciences Education, 26, 847–863.

Martin Eklund et al. (2021). “MRI-targeted or standard biopsy in prostate cancer screening.” New England Journal of Medicine, 385(10), 908-920.

Markus Feufel & John Flach. (2019). “Medical education should teach heuristics rather than train them away.” Medical Education, 53(4), 334-344.

Henrik Grönberg et al. (2015). “Prostate cancer screening in men aged 50–69 years (STHLM3): a prospective population-based diagnostic study.” Lancet Oncology, 16(16), 1667-1676.

Bjørn Hofmann. (2023). “To consent or not to consent to screening, that is the question.” Healthcare, 11(5), 664.

Bjørn Hofmann, Lynette Reid, Stacy Carter, and Wendy Rogers. (2021). “Overdiagnosis: One concept, three perspectives, and a model.” European Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 903-912.

Christopher Veal et al. (2026). “A protocol for the development of a core outcome set for adults with depression.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 191, 112119.

Per-Henrik Zahl, Mette Kalager, Pål Suhrke, and Erik Nord. (2020). “Quality-of-life effects of screening mammography in Norway.” International Journal of Cancer, 146(8), 2104-2112.