Resource Reallocation

Critics worry mass screening programs divert resources from more effective interventions; this logic belongs in causal models

This may well be in a Herbert Simon-era textbook already, but it struck me yesterday that resource reallocation deserves explicit representation in causal diagrams for mass screening programs.

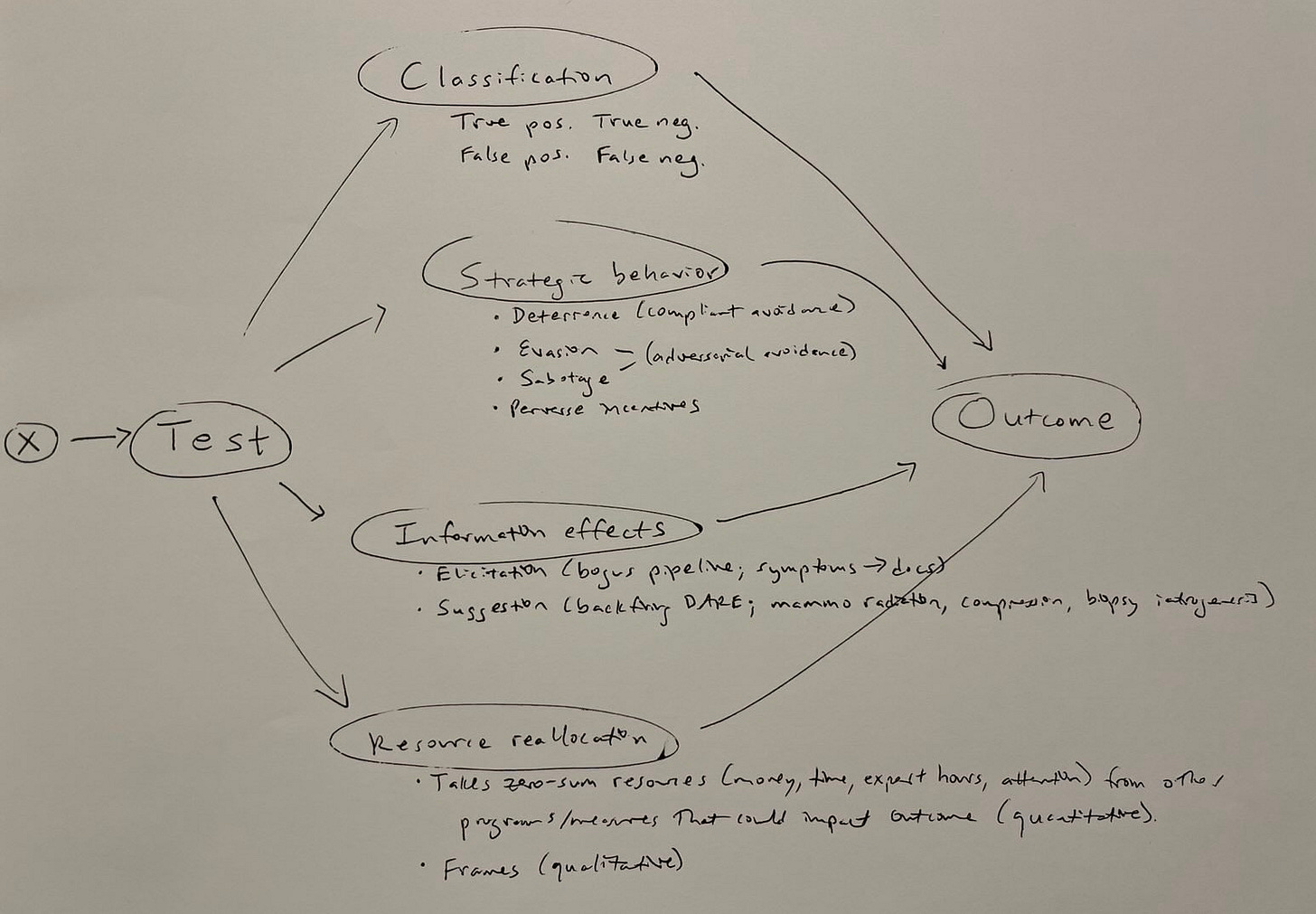

Here’s the updated DAG (directed acyclic graph, the official walking stick of the causal revolution).

In this DAG, classification breaks down into true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives. Strategic behavior features deterrence (compliant avoidance), evasion and sabotage (adversarial avoidance), and responses to perverse incentives. Information effects include elicitation (the so-called bogus pipeline effect) along with suggestion (which might include iatrogenic effects). Resource allocation includes a quantitative component in which programs take zero-sum resources from other measures that could impact outcomes, and a qualitative component in which the program frames the problem in a particular way that could also impact outcomes. (The latter is what I think Meredith Whitaker was talking about, for instance, in her criticism of the base rate bias criticism of Chat Control.)

Here’s the updated DCG (directed cyclic graph, allowing feedback loops). It shows feedbacks in red and moderating effects in orange. (Though I suspect moderating effects don’t belong here formally.)

In security screenings for low-prevalence problems like polygraphs and Chat Control, one of critics’ paramount worries is that overwhelmingly false positives will swamp investigative capacities — making it harder to follow up on serious, well-founded concerns.

Similarly, in medical contexts like mammography and PSA testing for breast and prostate cancers, critics worry that resources spent on mass screening could be more effectively allocated elsewhere. This is not just about money, but also about the possibility that some approaches could be better than others — saving more lives overall while also increasing instead of decreasing quality of life for many.

For example, education and support resources to reduce or stop substance use (especially alcohol), and improve diet and exercise, might work better on those terms. We also need more research into the possibility that cheap, widely available, and commonly used anti-inflammatory drugs like aspirin and ibuprofen might reduce the prevalence and grade of diagnosed cancers including breast and prostate cancer — research it would be costly to conduct. (There is a vast array of evidence, however, suggesting these possibilities are worth exploring.)

Of course, these ideas aren’t new. I just haven’t seen them put into causal diagrams. Drawing resource reallocation as one causal mechanism among others in these programs helps clarify how these paths may affect outcomes.

On one hand, drawing the logics out shows that simply illustrating the base rate fallacy (cf Fienberg) isn't enough to establish net harm from programs of this structure. Deterrence and elicitation could still make polygraph programs net effective.

On the other hand, it also suggests that the potential dangers of programs of this structure may go beyond what we see in gold-standard net effect assessments like the Harding Center’s Fact Boxes. Resource reallocation could make programs that look slightly net beneficial on specific cancer deaths at the societal level, actually incur net losses.

We need to count bodies along every causal pathway. And ideally, we probably also need to have a way of envisioning how these effects interact.