Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

Did I accidentally kill the most popular scientific argument against mass surveillance?

Maybe it was just my favorite argument…

The Base Rate Argument

Technology can’t escape math. Setting a lower detection threshold to reduce false positives leaves too much abuse undetected; raising accuracy to detect more abuse generates too many false positives. That’s why the National Academy of Sciences concluded mass polygraph screening of National Lab scientists offered “an unacceptable choice”. Mass digital communication screening faces the same dilemma.

Sounds like an open-and-shut case. Mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems, like polygraph programs for spies at National Labs and mass digital communications surveillance for child sexual abuse material, are doomed to backfire — undermining the very security they’re intended to promote.

Everyone wants the same thing — security. There are no value conflicts here. This is just an empirically, mathematically wrong way to go about achieving an agreed end.

Don’t like it? Don’t blame me; blame the universal laws of mathematics. Doesn’t suit your political tastes? It’s not political; it’s statistical. You get the point.

It’s such a popular point among contemporary scientists that, as of July 2023, hundreds of scientists and researchers agreed, signing an open letter against the EU’s proposed Child Sexual Abuse Regulation (“Chat Control”) expressing the view that:

As scientists, we do not expect that it will be feasible in the next 10-20 years to develop a scalable solution that can run on users’ devices without leaking illegal information and that can detect known content (or content derived from or related to known content) in a reliable way, that is, with an acceptable number of false positives and negatives.

UK security and privacy researchers published a similar open letter in response to the analogous Online Safety Bill, which passed in October 2023. There’s also similar opposition to the analogous U.S. Kids Online Safety Act, which still has not passed. (It was passed by the Senate in July 2024, but did not pass in the House before the end of the session.)

Political Heat: Chat Control in 2025

Chat Control has sparked an ongoing years-long political battle. Under the new 2025 Polish Presidency of the EU Council, member states recently evaluated and rejected an amendment that would have made scanning of private communications voluntary for service providers, saving the possibility of mainstream access to end-to-end encryption. A majority of EU member states, it seems, would prefer mandatory scanning.

Maybe they didn’t hear the argument that mass surveillance backfires because of math. That you can’t beat the base rate. Or maybe they don’t believe it. Or maybe, just maybe, they even think it’s wrong… And maybe they’re right.

The Math Still Matters

Some people don’t think the math matters that much, anyway. For example, Signal president Meredith Whitaker told CyberScoop she thinks focusing on the math distracts from the broader issue of child abuse, how it’s usually perpetrated by a trusted authority figure, and we should help real kids in real life instead of focusing on an online bogeyman.

But whether or not a program like this degrades exactly what it seeks to protect really is important if we want to help kids in real life, as I’ve written previously. Either mass screenings like Chat Control would overwhelm investigative capacities by flooding them with false positives, net degrading child safety — or they would actually advance it. This is an empirical question, and the answer doesn’t have to determine free societies’ political choices. But it should sure as hell inform them.

The scientists who wrote and signed the open letter opposing Chat Control thought they had the answer:

At the scale at which private communications are exchanged online, even scanning the messages exchanged in the EU on just one app provider would mean generating millions of errors every day. That means that when scanning billions of images, videos, texts and audio messages per day, the number of false positives will be in the hundreds of millions. It further seems likely that many of these false positives will themselves be deeply private, likely intimate, and entirely legal imagery sent between consenting adults.

This cannot be improved through innovation: ‘false positives’ (content that is wrongly flagged as being unlawful material) are a statistical certainty when it comes to AI. False positives are also an inevitability when it comes to the use of detection technologies -- even for known CSAM material. The only way to reduce this to an acceptable margin of error would be to only scan in narrow and genuinely targeted circumstances where there is prior suspicion, as well as sufficient human resources to deal with the false positives -- otherwise cost may be prohibitive given the large number of people who will be needed to review millions of texts and images. This is not what is envisioned by the European Commission’s proposal.

But what if they were wrong?

Are the Scientists Wrong?

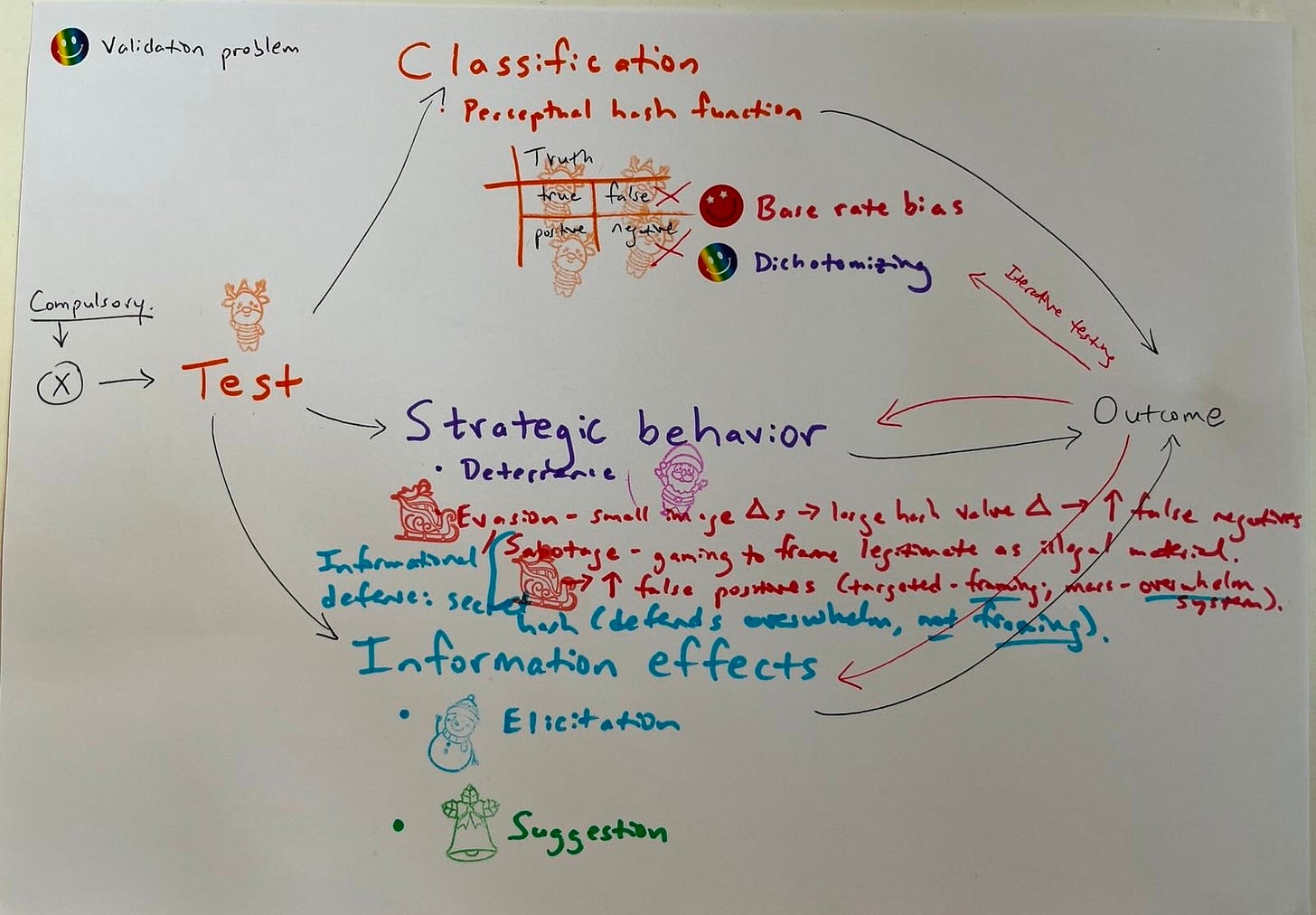

What if the most popular scientific argument against the current wave of proposed Western mass surveillance is flawed like Fienberg/NAS’s polygraph report was flawed? Both arguments deal with programs that share an identical mathematical structure — signal detection problems under conditions of rarity, persistent uncertainty, and secondary screening harms. Both arguments are missing causal diagramming. The same basic structural logic applies, for which we can draw the graphs. Again:

Though I haven’t seen these drawn elsewhere (tho presumably they have been), anyone interested in this debate will have heard various facets of all this discussed by experts on both sides: Deterrence could work, but we’re not sure how it adds up. Dedicated attackers gaming the system could in turn be gamed — but that dynamic could also backfire if criminals make their own encrypted messaging worlds and don’t get Pwned. Information effects could also factor in: Dumb criminals think you’ve got them and confess — great.

And — the real kicker — iterative screening could change the structure of the calculations entirely. Fienberg/NAS and scientists opposing mass digital screenings like Chat Control assume a one-off testing situation. But, in reality, many security screenings operate iteratively — incorporating new signals over time, refining priors, and adapting. That opens the door to different paradigms with different trade-offs…

A Bayesian Reframe

Different paradigms like Bayesian search, as is classically used to look for a missing boat or plane (and one could imagine being used to similarly look for a spy). Or recursive Bayesian estimation as is used in a number of navigation and tracking contexts. Or dynamic Bayesian networks, which can model dynamic systems at steady-state by developing on different time steps. These might be used (for instance) to try to distinguish cyberattacks from safety incidents at nuclear power plants — a topic of increased practical importance in the context of Russia’s hybrid warfare campaign.

To be sure, I need to learn pretty much everything about all these things.

But it would be weird if mass security screenings were one-off instead of using an alternative paradigm like one of these. Polygraph programs certainly aren’t one-off; it’s typical for one inconclusive or failed polygraph to lead to another. It’s not clear why we would expect mass digital communications surveillance to be different. It might make more sense for flags to be interpreted in the context of patterns, rather than in isolation. If these programs aren’t being designed that way, then maybe they need to be redesigned.

Maybe that’s why Palantir, the IDF, and other companies and state actors using mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems don’t come back and say so when critics say they have a false positive problem. First, of course they do; but that doesn’t tell us how multiple such causal elements net out.

Second, maybe that problem isn’t not half as bad as critics think it is, because testing is iterative rather than one-off. But you wouldn’t want to lessen the screening’s power to deter bad actors or make dumb criminals confess by coming out and saying that one failed screening isn’t going to hurt anyone. Or give away trade secrets that could change the information environment that’s part of that bigger causal picture.

So let’s just assume that the proposed screening is not a one-time affair. Rather, it’s an iterative process embedded in a dynamic system of attackers, deterrence, and changing priors. In that context, it doesn’t look so obvious what the net effects of programs of this structure are, even under conditions of rarity, persistent uncertainty, and secondary screening effects. At least, I would like to see it modeled starting with causal diagramming, and haven’t.

Rebutting the Opposition

The best of the open letters I’ve seen opposing client-side scanning is the EU one, for its detailed scientific arguments. The first press inquiry contact person listed on it is Carmela Troncoso, Associate Professor and head of the SPRING Lab focused on Security and Privacy Engineering at EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland, and a scientific director at the Max Planck Institute for Security and Privacy in Germany.

In a recent Wired article, Troncoso told the magazine “The trend is bleak. We see these new policies coming up as mushrooms trying to undermine encryption” (“A New Era of Attacks on Encryption Is Starting to Heat Up,” Matt Burgess, March 14, 2025).

The opposition sees client-side scanning and other mass surveillance measures as threats to privacy, liberty, and the ability of liberal democratic societies to defend themselves against authoritarian abuses.

They may be. But that’s a different question than whether they further or undermine security, as the opposition also argues. So let’s plug Troncoso’s open letter’s arguments into the causal diagram to see where they fit, whether the structure changes, and whether we know how the effects net out…

The Perceptual Hash Debate

Under the heading “1. Detection technologies are deeply flawed and vulnerable to attacks,” Troncoso et al introduce a number of concerns about how Chat Control could backfire. They reason that “the only scalable technology” to use for such scanning would transform “the known content with a so-called perceptual hash function and [use] a list of the resulting hash values to compare to potential CSAM material.”

Perceptual hashing, based on Marr & Hildreth’s “Theory of Edge Detection” (1979), uses a fingerprinting algorithm to identify media based on (1) multi-scale edge detection (looking at intensity changes over multiple scales) using (2) the Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) Operator (the second derivative of a Gaussian function) for smoothing (less noise) and edge enhancement (more signal), and constructing (3) a “raw primal sketch” combining zero-crossing segments from multiple scales, which provides a picture of the image’s intensity changes.

This is a great signal detection hack. Bonus points for introducing the phrase “raw primal sketch.”

But the question is whether false positives still overwhelm mass screening if this technique is used to detect child sexual abuse material in digital communications or the cloud or whatever. That’s an empirical question.

Ignoring the possibility of deterrence, Troncoso et al point out (though these terms are mine) that the negative side of strategic behavior could take two forms: evasion and sabotage. (My earlier diagram missed the latter.) In evasion, small image changes could result in large hash value changes to increase false negatives. In sabotage, gaming to frame legitimate material as illegal could increase false positives. In targeted sabotage, this looks like framing (e.g., as when an authoritarian state wishes to discredit and imprison a dissident on false charges). In mass sabotage, this looks like a dedicated attacker overwhelming the system to make it effectively unusable.

There’s an information defense against the latter: keeping the hash secret. Troncoso et al don’t think it would work, because “In the case of end-to-end encryption, the hashing operation needs to take place on the client device.”

This argument confuses two different forms of relevant secrecy. Keeping either the algorithm or the hash list secret is part of the defense against evasion or sabotage (like poisoning or reverse engineering the hash space). Client-side scanning can’t keep the algorithm secret if it needs to live on your phone. But most perceptual hash algorithms aren’t secret anyway (e.g., pHash, aHash, dHash). That doesn’t mean all the algorithmic tweaks or the hash database have to be out there.

On one hand, hash database secrecy can protect against mass sabotage — an adversarial attack flooding the system with false positives. On the other hand, it can compound the risk of authoritarian regimes framing dissidents. And, if the system depends on secrecy, exposure can break it…

“Security by Obscurity?”

That’s why Troncoso et al and others criticize “security by obscurity.” But they’re importing that phrase from classical cryptography, where it pertains to algorithm secrecy — which is rightly considered bad practice.

Perceptual hashing is a different context. It’s a signal detection technique designed to identify similar content — and its resilience against evasion or sabotage might very well depend on keeping some implementation details obscure. The question isn’t whether obscurity is ideal — it’s whether, in this context, it can help prevent gaming or flooding. Some level of secrecy in implementation detail or the hash list is required to bolster the algorithm’s resilience to adversarial attacks (evasion/sabotage). That’s a design trade-off, not a flaw, per se.

The open letter’s critique may be misunderstood if it doesn’t distinguish between keeping the algorithm secret (not possible or required in client-side scanning) and keeping the hash list secret (to protect against evasion/sabotage). We need to be clear that the real risk of this form of secrecy is feared state abuse. And then we need to follow the logic here out: there might be ways to design checks against that threat.

Similarly, there’s no math in the open letter backing up the claim that false positives would overwhelm the system. There’s no recognition of the open empirical question of how classification, strategic behavior, and information effects net out.

In the second substantive section, “2. Technical Implications of weakening End-to-End Encryption,” the authors are clear that governments could abuse client-side scanning infrastructure to target dissidents by manipulating hash values, and that “security by obscurity” would be necessary for any such system to function. There’s no recognition that manipulated hash values would get reality-checked (e.g., when police actually collect suspects’ phones to look for child abuse images) — so a whole chain of evidence would have to be falsified at multiple points in a legal process in order for a manipulated hash value to have criminal justice consequences. At some point, evidence gets shared and shown as part of legal processes; obscurity, at least in theory, ends in court (if not before).

In the third substantive section, “3. Effectiveness,” the authors again express concerns about the negative strategic behavioral effects of such a program. “We have serious reservations whether the technologies imposed by the regulation would be effective: perpetrators would be aware of such technologies and would move to new techniques, services and platforms to exchange CSAM information while evading detection.”

While this is a valid concern, by the same (causal mechanistic) token, there are also positive strategic behavioral effects to consider (i.e., deterrence). We don’t know how all the different causal effects would net out. And we have to consider the iterative nature of possible mass security screenings that don’t just do one-off tests.

Overall, the open letter claims all detection technologies are doomed to be overwhelmed by false positives. But without causal diagramming or modeling to get the logic (first) and math (later) right, we don’t know this. There are also possible positive strategic behavioral and information effects that the letter ignores, along with iterative screening strategies that have implications for the false positive problem.

A Chat Control Causal Diagram

Here is the directed cyclic graph (DCG) filled in with the Chat Control specs discussed above. It shows that, yes, we have to worry about base rate bias, evasion, and sabotage. But we also need to consider the effects of iterative testing, deterrence, and elicitation. We don’t know how these causal mechanisms net out, and we need to be honest about that in discussing these sorts of programs.

Or, more neatly:

Why It Matters

Getting the causal logic and the subsequent math less wrong are key to resisting bad programs and building good ones.

I am not a proponent of mass screenings for low-prevalence problems in general — though some, like England’s recent vertical transmission elimination of hepatitis B, have been hugely successful. Nor of mass security screenings in particular. To the contrary, I’ve written extensively warning about the potential dangers of programs of this structure, and signed Troncoso et al’s open letter. I’ve been thinking about the dangers of this structure for years, and am still puzzling over it.

But I’m also a mother who would give up some privacy to help keep kids safe — if it worked. And a scientist who wants to be honest, and see other scientists be honest, about what we do and don’t know.

I’m also aware that opposition to proposed policies must be rooted in sound logic, or it risks being ignored or outmaneuvered. My goal here is to test the strength of the argument — not weaken the opposition. It’s also to critically self-reflect…

Reconsidering Client-Side Scanning Lawsuits

It seems to me now that my December analysis of principal-agent problems in the context of client-side scanning lawsuits was too black-and-white, and too dark on motive. Too black-and-white, because we don’t know how the causal effects net out. And too dark on motive because, even if they stand to make a lot of money, we can’t expect the lawyers or other people advising child sexual abuse victims suing Apple to know something that scientists don’t know, either. (They’re suing Apple over its failure to implement the client-side scanning system NeuralHash to detect child sexual abuse material in iCloud, much like Chat Control would use AI to detect it in EU digital communications.)

Political Abuse Potential Is Real

This is all not to bracket or dismiss the other problem of the proposed mass surveillance: the concern that technological infrastructure for it will invariably be abused, generating repression of legitimate dissent, as Apostolis Fotiadis and others have argued. Ross Anderson, the late Cambridge University security engineering professor and digital rights campaigner, told Fotiadis that the potential for security agency manipulation of these sorts of AI scanning infrastructures was under-appreciated.

As Namrata Maheshwari, encryption policy lead at digital civil rights nonprofit Access Now, recently told Wired, states are pressuring for a lawful access backdoor, client-side scanning, and outright bans on encryption technologies. Some civil libertarians tend to see them all as threats to privacy. But a recent Joint Declaration of the European Police Chiefs criticizes this view:

Our societies have not previously tolerated spaces that are beyond the reach of law enforcement, where criminals can communicate safely and child abuse can flourish. They should not now…

… we do not accept that there need be a binary choice between cyber security or privacy on the one hand and public safety on the other. Absolutism on either side is not helpful. Our view is that technical solutions do exist; they simply require flexibility from industry as well as from governments…

We therefore call on the technology industry to build in security by design, to ensure they maintain the ability to both identify and report harmful and illegal activities, such as child sexual exploitation, and to lawfully and exceptionally act on a lawful authority.

This seems like a sane rebuttal to dichotomania (false binary thinking) and uncertainty aversion, common cognitive biases that are known to affect scientists along with everybody else. Though, at the same time, it assumes that the problem is solveable.

That may be true. But belief in solvability isn’t the same as demonstrating it.

Neither side wants to acknowledge that, apparently, we don’t know whether the problem is solveable, or not. If we knew, at least in my imagination, both sides would show their work. We would look at the logic and the math. The issue would be decided.

But it can’t be. Chat Control remains in limbo. Maybe that’s because neither side is drawing out the logic to answer the core question — do programs like this work, or backfire? — in the first place.

An Ecosystem View

In a healthy sociopolitical ecosystem, these sorts of arguments could continue while laws were made and remade, infrastructure changed, and pendulum swings in information security came and went with whistleblowers, technological innovations, and other tides.

There would probably remain, regardless, a base level of mass surveillance enabled by its technological possibility. “Good you don’t mind it,” quipped a resident expert when I rambled on about this before writing it down — “because mass surveillance is here to stay.”

Still, there will always be people in favor of this sort of infrastructure (police: let us go after the baddies better) and people against it (civil libertarians: let us constrain the state’s abuse potential).

We shouldn’t seek an objectively right answer to their political conflict, insofar as it’s a value conflict. Science can’t help here.

But the question of what works to achieve certain ends, like child protection, is a different one. We should try to answer it.