When Covid vaccines first became available for children near Berlin, we took our then-infant son by Bahn to the end of the line, and then by cab to a practice that had an assembly line of children and parents going in one open door and out another. For over a year after this, our little guy would cry when he had to ride in a car — even to the mall to visit Santa — fearing a shot.

Later, I would realize this was more than a tactical mistake: The possible risks of vaccine injury, especially myocarditis for young males, may outweigh the risks of infection. As I wrote previously, we don’t know and would need randomized trial data comparing post-infection versus post-vaccine outcomes to find out. We don’t have and are unlikely to get that data.

As a mom, my first duty is to protect my children. In this case, my job was to protect my son from possible net harm from intervening, when not intervening was pretty safe. Covid in kids is generally mild, and we weren’t hitting the party scene (or at least, I was trying my best to keep our household out of it). So uncertainty about net effects clearly should have tipped the scale to the side of not giving the baby the shot.

Being the sort of person who keeps running lists of mistakes in her head, I’ve written about this. But not published the essay, because I’ve not been able to convince some very smart people of the fact that this was definitely a mistake, we all should have known better (some of us did), and we shouldn’t do it again.

We should look for evidence of net benefit before intervening. Proponents should bear that burden of proof. This would protect society from a massive amount of harm.

It’s not the facts that are missing. It’s the ability to see them. Being regularly crippled by my own apparent inability to see things from sociopolitical realities to missing vitamins that are right in front of me, I find this very interesting.

Why do smart people disagree about this? And why can’t I convince anyone who disagrees with me, with the evidence? It’s not an edge case.

Just do something

One of the obvious explanations is the will to just do something.

It’s not uncommon that we want to do something to solve a problem, when doing nothing would be better. I’ve struggled to convince legislators and other experts of this in policy conversations. Even faced with evidence that we can’t escape the universal laws of mathematics and can hurt a lot of people trying, policymakers don’t like the idea that the best tech used by the best experts may actually make things worse than doing nothing at all. They can’t see themselves making that argument to constituents, experts, or other policymakers. It’s a social fail.

Doing nothing at all (TM) doesn’t get or keep anyone elected, though that’s the one ballot I would be happy to run on. (And, being a single mom of two young kids, that’s a campaign promise I could keep!)

So there’s this well-documented intervention bias in policy, medicine, and beyond. And it would make sense that mortal terror that one’s kids could get hurt could make people both dumber and more likely to intervene, when doing nothing is smarter.

Shortcuts

We all take shortcuts all the time, because we can’t investigate primary source materials in relation to every important life decision for us and our loved ones. There’s too much information coming at us too fast. Modern societies are too complex. We have to delegate trust to get stuff done. And that means using heuristics (shortcuts), like trusting our tribes’ consensus.

The U.S. progressive Covid consensus was that vaccination was good, including for healthy kids, because the virus was so nasty.

The above passage about Covid risks to kids comes from Paul Offit’s 2021 You Bet Your Life: From Blood Transfusions to Mass Vaccination, the Long and Risky History of Medical Innovation. It sounded pretty scary to me. The source was credible (I thought): Offit is a pediatrician, writer, co-inventor of a rotavirus vaccine, and professor of Vaccinology and Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. He was the only CDC advisory panel member to vote in 2002 against smallpox vaccination in the context of bioterrorism concerns, due to his perception of its net risk.

But he also has multimillion dollar conflicts of interest, including reportedly earning millions from the rotavirus vaccine he co-invented that was then sold by Merck, while drawing a salary from a Merck-sponsored position and sitting on the CDC panel that voted to recommend that same rotavirus vaccine. These earnings don’t make him wrong. But it would be weird if that amount of money didn’t motivate anyone’s good-faith reasoning.

To be fair, Offit’s book doesn’t say “vaccinate your child early and often against Covid.” But it’s not a big leap from “this virus does heinous things to children that no other virus does” to “there’s a vaccine and here’s my baby’s arm.”

Changes and unknowns

Then, back in September 2023, Offit appeared to have changed his mind. I wrote:

Offit has since joined a chorus of journalistic and scientific voices recognizing the U.S. as an outlier in continuing to recommend or mandate annual Covid vaccines for healthy young people. These policies constitute a mass preventive intervention for a low-prevalence problem, severe Covid in healthy young people. This intervention is not without costs and possible risks — known and unknown.

This got me thinking about unknown unknowns and unknowners, a rabbit hole into which my draft and I fell, never to return. (This is, as Heraclitus would say, a different me writing.)

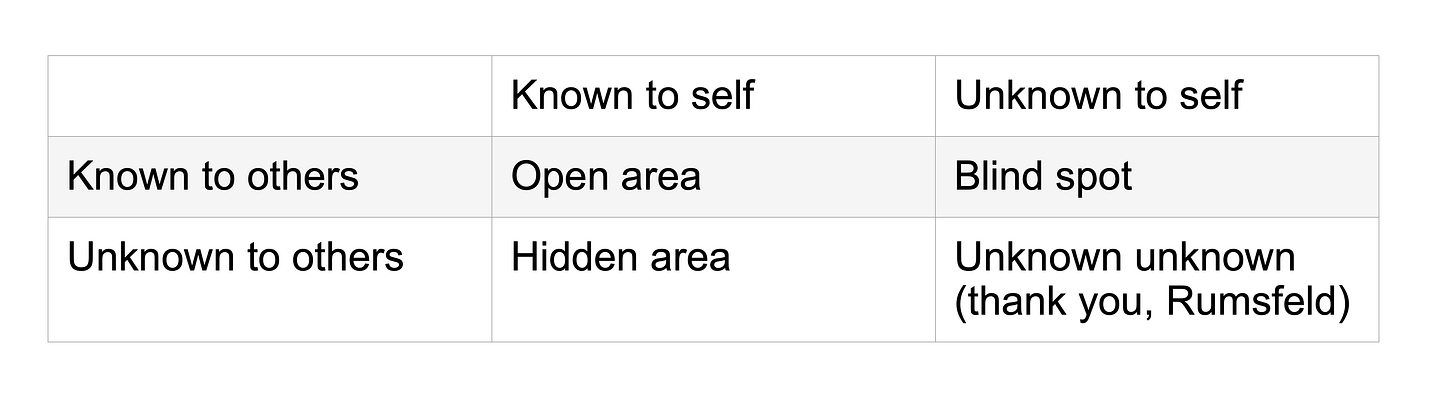

You see, during America’s failed Iraq War, former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld popularized the phrase “There are unknown unknowns.” This phrase comes from the bottom right quadrant of the Johari window, a heuristic that American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham developed to help people, help themselves. It’s a dyadic (two-part) model of information asymmetry — known and unknown, self and others. It looks like this:

The Johari window is about knowledge, but my mistakes are often not just not knowing what I didn’t know. They’re also thinking I know something that isn’t so. Like that time I thought I had done my homework on infant feeding, but it turned out the medical literature was wrong.

It’s harder to change misperception with new information than it is to change ignorance with knowledge. So when I accidentally starved the very same then-infant son doing the recommended “exclusive breastfeeding,” it took me a while to figure out just how stupid I had been.

In this way, misperceiving is worse than not knowing. So we might consider (as probably someone has already) a complementary perception model alongside the Johari window’s knowledge model of information asymmetry:

My first intuition was that the perception model builds out in depth from the knowledge model. But there are different ways to think about this, and they don’t all make conceptual sense to draw that way.

Johari is a 2x2 with binary variable values self-others and knowledge-ignorance. Jopshari (say “J’oops! sorry”) could be a 2x2 with binary variable values self-others and knowledge-perception (implying a distance - misperception), or perceived as knowledge versus perceived as ignorance, or perceived versus misperceived. Conceptually, perceived-misperceived seems like the truest analogue to knowledge-ignorance, and the most informative additive choice.

Alternately, one could argue for recoding all knowledge as perception, because really knowing anything is hard. Although confirmed facts exist, this is a heuristic and certainty isn’t modal; so maybe we leave it out. In that case, the 2D Johari model becomes about perception instead of knowledge, and the depth space misperception iteration is a bit cleaner an extension because it’s all perception in one dimension and all misperception in another.

I would prefer to leave the standard Johari model unmodified (it’s more informative; confirmed knowledge exists), and try to stretch out in different planes for both perception and misperception as distinct from knowledge. One could also envision more and more planes for more and more levels of thinking about what other people think we think we know (that may or may not be so). This has implications in intelligence, marketing, PR, social psychology, and other seedy fields. Perhaps the most controversial is the context of information environment management, e.g., when tech companies mass-screen social media posts for misinformation. Probably this is not the best way to sketch this, but it might look something like this:

It seemed to me that I couldn’t build this out of puzzle-piece foam with a 3D printer, so I probably didn’t know what I was talking about.

And then, somewhere between September 2023 and May 2025, Offit changed his mind again. He went from recognizing the U.S. was a global outlier in recommending annual boosting for healthy kids including those with natural immunity, to calling the new policy not recommending it part of a war on kids.

Hyperpolarization

Offit is far from alone in demonizing the other side. It seems like few scientists want to break the spiral of silence by commending or expressing hope for some of the ongoing reforms in U.S. scientific institutions, from the NIH ensuring it doesn’t fund the sort of gain-of-function research that may have caused the pandemic, to the Executive Order prioritizing badly needed science reform or the defunding of NSF-sponsored bias research that, it must be said, faces serious methodological problems.

It seems obvious a lot of people hate having their funding cut, as one would expect. And of course these reforms are imperfectly proposed and will be imperfectly executed. They’re being done by human beings.

Still, if I say something like this, the responses I’ve gotten in substantive political conversations for the past half year or so with people close to me tend toward “Well, Hitler built great highways.” This seems grotesquely ill-informed. But also impossible to counter, in the sense that piping up with disagreement to the apparent majority of other people’s firmly held views seems likely to end in little more than reputational cost and frustration to me.

I’m always writing about how scientists who stick out get hammered, with spin science shaped by powerful interests and dominant narratives; alternate possibilities in complex, ambiguous evidence getting filtered out despite reformers’ longstanding demands we do better; and reform efforts disproportionately targeting dissenters. So why stick my neck out?

Just curious. Bemused. Stupid, I guess.

Why is it so hard for us to get that “This is water,” in David Foster Wallace’s parlance? That, when we think we know something, that knowing is part of our sociopolitical position, and it could contain bias and error? So we could be wrong, and people who think they know something else could be onto something?

Before peering into another methodological rabbit hole about how and how much to criticize self-proclaimed “evidence-based” policy for miscasting good methods as uniform or neutral when they’re plural and political, I wrote this now-rejected essay (below) on how actually great recent FDA and CDC Covid vaccination guideline changes seem.

And then I realized, I have very few readers, and that’s probably a good thing. My science writing isn’t gelling in the sense of making much income, and I’m drawn to controversial stuff. My science isn’t gelling beyond insights guaranteed to piss everybody off. (E.g., I have made dedicated efforts to give both surveillance opponents and surveillance proponents reasons to hate me.) If either of these efforts were to succeed, I’m told I would get hate mail at best, threats at worst. So maybe it’s a good thing I’ve not gotten any farther?

Either way, it’s probably time to transition this to a blog about my adventures in skilling up in tech to get a job doing something boring from home while my kids are young. I so much enjoy thinking and writing, and hope to be able to have fun doing it on that terrain. But I understand if you don’t want to read about my adventures in SQL and Python, or whatever other boring tech thing I figure should top that teeming, long-neglected to-do list, if I even do wind up writing about it here next. I don’t know what I was thinking trying to write for a broad audience in the first place, being the kind of person who finds correcting a math mistake exciting.

Now, hot from the cutting-room floor…

The FDA Course-Corrects Covid-19 Vaccine Policy

Reports of the death of the U.S. public health establishment have been greatly exaggerated. The FDA's new Covid-19 vaccination guidelines advise older and at-risk groups to get annual Covid vaccines, but recognize that existing evidence does not establish net benefit for other groups. This marks a shift from presumption of benefit from annual boosters for low-risk groups, to requiring proof — a widely accepted scientific evidentiary standard.

The new guidance brings the U.S. in line with other countries, such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, and Switzerland, where the vaccine is recommended only for people age 65+ and those at high risk of severe Covid. The reform requires that pharmaceutical companies now establish the safety and efficacy of their products in preventing clinically important harm such as relevant hospitalization or death. This incentive structure shift is exactly what regulators are supposed to do, countering perverse incentives such as corporate profit with standards that protect consumers and promote the public interest.

Prior U.S. policy granted authorization for Covid vaccines to everyone over the age of six months. This was globally anomalous and particularly contentious for healthy young males, for whom vaccine-associated myocarditis may have caused net harm. Given that COVID infection in children is generally mild, it will be hard to show benefit in this group.

The U.S.'s prior Covid vaccination policy similarly made it an outlier in prenatal care. In the first trimester, both infection and vaccination may incur substantial risks of major birth defects. Vaccination during pregnancy may also incur substantial miscarriage risk. Peer countries, like Germany, have long recommended Covid vaccination for pregnant women only if they have an existing underlying illness, and then only from the second trimester. Otherwise, basic immunity — three pathogen exposures, at least one from vaccination — is considered sufficient.

Covid vaccination in pregnancy may also substantially increase the risk of stillbirth, though the effect is similarly uncertain and the absolute risk small. As with healthy kids, in the absence of proven net benefit, promoting Covid boosters to pregnant women risks net harm. Many scientists and methodologists argue that proponents of new interventions should be required to demonstrate net benefit before widespread implementation, especially in low-risk groups.

Yet even this new policy, better aligned with scientific standards, keeps the U.S. on the more aggressive end of the Covid vaccination policy spectrum with respect to pregnant women. The benefit-harm balance is uncertain and may hinge on how well a patient is able to avoid infection. On this complex terrain, flattening uncertainty into one-size-fits-all advice doesn’t serve patients.

In light of such complex realities, the new guidance from FDA and CDC permits patients to decide with their doctors if they have an underlying medical condition that increases risk of severe Covid and thus warrants vaccination. The expansive 23-item CDC list of such conditions includes depression, physical inactivity, and pregnancy. This confers access to the vaccines to around 100-200 million Americans — a third to half of the population.

The CDC provides usage recommendations, which it recently updated with a change in its recommendation language for pregnant women and healthy kids from "should" to "may." The FDA’ s role, in turn, is to authorize vaccines on the basis of safety and efficacy evidence. Recent changes from both public health institutions reflect a unified, evidence-based policy shift away from blanket boosting recommendations, to recognizing widely acknowledged uncertainty about net benefit from vaccinating younger people, especially pregnant women and healthy kids.

Nonetheless, the new policy has provoked fierce backlash. For instance, venerated vaccine expert Paul Offit called it part of "RFK Jr.'s War on Children" and accused the CDC of making “it difficult for pregnant women to protect themselves against Covid.” Such rhetoric ignores the evidence's complexities and uncertainties, as well as the realities of vaccine access. It also risks further eroding public trust in experts and institutions.

Reactions like Offit's are understandable given concern for preventable deaths, but reflect the pervasive cognitive and emotional distortions that plague us all as human beings. While Offit concludes "the data are clear," scientific evidence is often complex and ambiguous. Reasonable people can disagree about how to interpret it. Indeed, most countries have long interpreted it in an altogether different way from how we have in the US.

The new guidance applies epistemic humility in an age of scientific polarization. As Prasad and Makary write, it's uncertain whether repeated vaccination, especially among low-risk people and those with natural immunity, confers benefits.

Where proponents of the previous vaccine policy tend to promote vaccine acceptance as a binary, the current FDA leadership argues that this black-and-white position may increase vaccine hesitancy and refusal. Proponents of the prior policy tend to see the vaccine-hesitant as needing clearer direction from credible authorities about the right choices. Conversely, reformers like Prasad and Makary, leading medical methodologist Peter C. Gøtzsche and rheumatology PhD, health sciences researcher, and investigative reporter Maryanne Demasi, and others tend to see different vaccines as — like drugs — offering different risks and benefits for different groups to be evaluated in line with changing evidence. In this view, it's medical paternalism and state overreach that contribute to valid public mistrust, leading sometimes to an overreaction in refusal even of proven safe and effective vaccines such as that for measles–mumps–rubella (MMR). But the FDA's policy centers on requiring randomized-trial evidence to approve vaccines for low-risk groups. In the context of rising global measles cases and deaths due to decreased vaccine uptake following the Wakefield fraud and vaccine misinformation — including from the CDC — we need to know what works to restore public trust. Gøtzsche argues that vaccine mandates are not proven effective. It appears, too, that Covid vaccine incentives may backfire, decreasing vaccine uptake. What if acknowledging uncertainty and respecting autonomy work better than enforcing contested norms?

Public health dean Sandro Galea has argued that the field must return to its European Enlightenment roots, weighing trade-offs, resisting groupthink, and correcting for progressive political bias. The new Covid vaccine guidelines answer that call. They enact a policy framework that encourages medical professionals to interpret ambiguous evidence with caution, protect the vulnerable from possible harms, and counterbalance bias and perverse incentives in the public interest. Whether they can restore public trust that may have been eroded by coercive policies like lockdowns and vaccine mandates remains to be seen.

A coding coda

And with that, I’m closing this chapter. Thanks for reading and supporting my valiant efforts to find truth and make enemies. We all have our talents. Maybe if I put as much effort into coding as I have into corrections and conflict, I can build some cool stuff.