Cringe Security

The causal revolution implies indeterminacy in net effects of security programs that affect liberty in sequential-feedback continua

Trying too hard to feel safe is so cringe. Like when your insecure boyfriend (or girlfriend) checks your phone “for your own good.” It’s awkward. It’s controlling. And worst of all, it kills trust. You want to feel free, not smothered; but you and your guy (or gal) want to feel secure in your love, too. The difficulty in striking this balance between freedom and safety is part of what makes relationships fragile.

Societies, too. State security apparatus can be like that insecure sweetie. So obsessed with safety, they accidentally smother and destroy the very thing they’re trying to protect — societies with civil liberties. Liberties like the rights to free speech and association. The right to ask questions — which might be seen as including conducting scientific research and engaging in investigative journalism without state interference or retaliation. The right to read texts and make phone calls of one’s own choosing without security forces getting in the way. The right to think one’s own thoughts, feel one’s own feelings, and move one’s own body, untouched by technologies designed to manipulate internal states, or even physically disperse (or displace) people.

This is more than just an intuition or a familiar argument in popular discourse. It’s also a logical consequence of drawing causal graphs for mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems. And it limits what science can tell us about whether these programs work.

Security Undermining Security

Critics often charge that mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems run the risk of ironically undermining security from within — by undermining the liberty that characterizes the society or other group they’re intended to protect. A classic example is mass surveillance chilling free speech. It may do so through self-censorship, by making dissidents afraid to voice their views. It may also do so through abuse, enabling police or other state actors to unlawfully target dissidents for prosecution for expressing legitimate dissent (e.g., by trumping up charges).

Many other security programs share an identical mathematical structure with mass surveillance, as they deal with signal detection problems. As such, they share structural vulnerabilities, for instance, to the base rate bias — as well as to this problem of security-seeking undermining security.

Maybe this is what we’re really talking about when we talk about bias and abuse in these programs. For instance, concerns about alleged racial bias in polygraphy, and perverse incentives for polygraphers to go after intimate information outside the scope of their purview.

This is different from the argument that the costs of false positives accrue to liberty and security alike, as I’ve previously argued. Because, in that story, we could still think about measuring costs and benefits to liberty and security from true and false positives and negatives — for instance, by coding crime survey data as reflecting those values. Or, maybe better, simulating uncertainty in estimated ranges thereof.

Whereas, in this story, we’re ultimately powerless to definitively, quantitatively assess net liberty and security effects. This limits what cost-benefits analyses of security programs can claim to do. They cannot claim to establish whether security programs net benefit or harm security.

The reason is that liberty and security are both causes and effects in a circular system. So, when you try to draw totalitarianism (aka cringe security) in the graph, eventually, you realize that you can’t. Here’s how this works…

Liberty: Security :: Free Will: Determinism :: Stochastic : Deterministic Universe (aka You Can’t Graph Totalitarianism)

This is Descartes’ drawing of the pineal gland, which he believed was the “seat of the soul,” joining mind and body. It appears in causal revolutionary Judea Pearl’s 1996 epilogue to Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, (NY: Cambridge University Press, p. 401-428, 2009, “The Art and Science of Cause and Effect” (h/t Sander Greenland). As I wrote previously, Pearl shows that:

whether it’s a deterministic or agentive human world depends on where you cut the drawing (p. 419-420, slides 36-38). Hone in on the subject, and the free will position holds. Center the outside world, and the deterministic position carries.

Like so:

In other words, the infamous free will/determinism debate (most recently voiced by Huberman/Sapolsky) is unresolvable: both agentive choice and structural determinants thereof are causes and effects in a circular system. In philosophy, this is generally recognized as hinging on the (similarly unresolvable) stochastic/deterministic universe question.

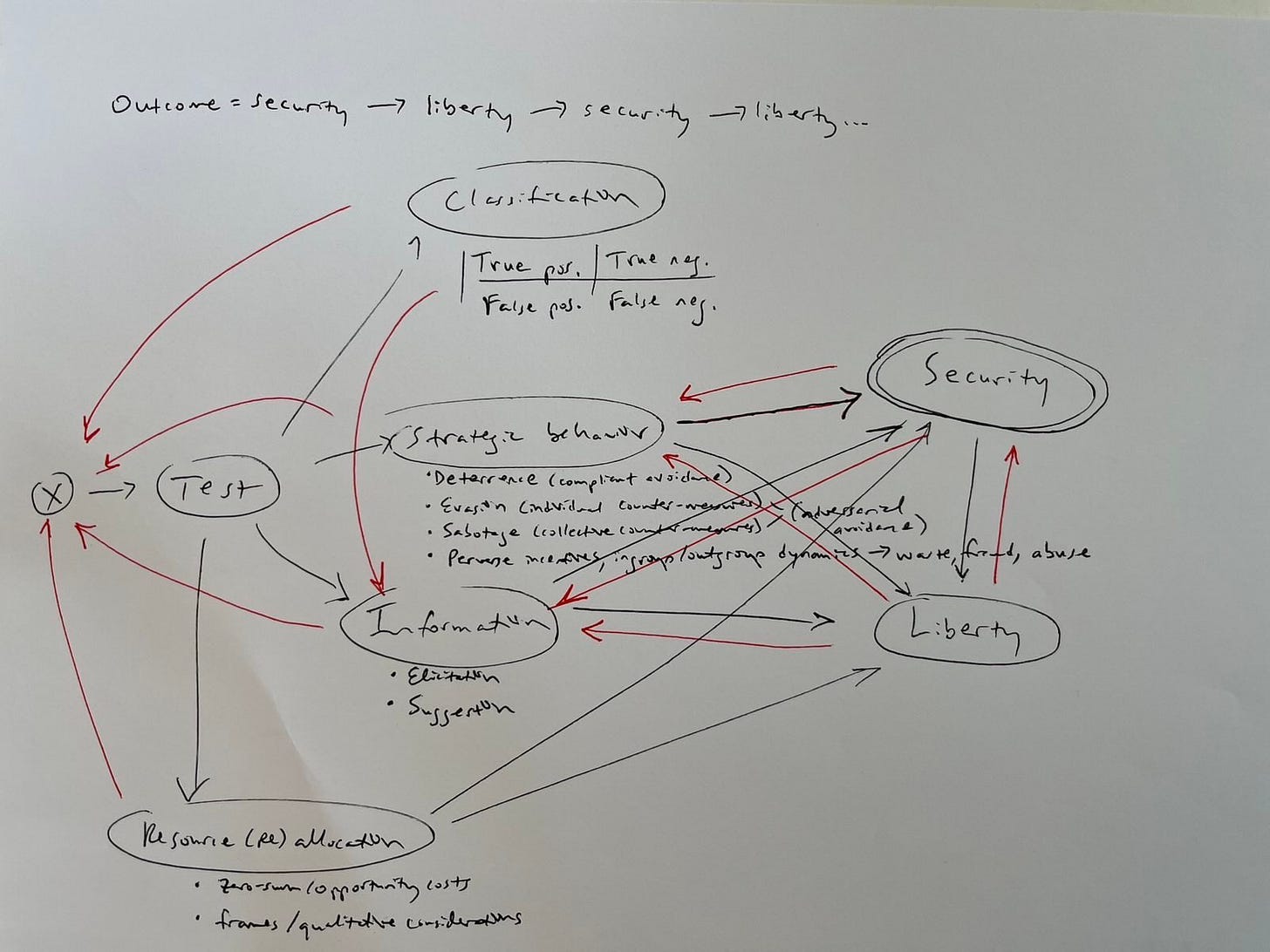

Liberty and security, like free will and determinism or stochastic and deterministic models of the universe, are all dichotomizations of sequential-feedback continua (in Greenland’s parlance). So the overall indeterminacy recurs, too. Sketched as a directed cyclic graph to account for the feedbacks (red arrows), that looks like this:

We can’t get the whole picture (we’re puny humans). So someone has to decide where to cut the frame. That cut is an interpretive choice with epistemic and sociopolitical dimensions. It cannot be a value-neutral one. We should be wary of assessments that ignore these limitations.

As with other such tests in the abstract, mass security screenings for low-prevalence problems can activate causal mechanisms other than just test classification, including the familiar deterrence Santa and elicitation snowman. As in the medical issue area, we have to worry about perverse incentives on both sides motivating “small fish” (individuals), “bigger fish” (an entire security-industrial complex and its adversaries, pictured here as octopi), and the “biggest fish” (societal-level predation, pictured here as circling sharks). As in all human endeavors, we have to worry about common cognitive biases including dichotomania (as in the dichotomization of the liberty-security sequential-feedback continua, and as represented by the rainbow smiley-face) and the base rate bias (star-eyed red smiley) in our expectations of what sorts of outcome spreads even highly accurate tests (Rudolf) produce.

(A future post will assess the generalizablity of this point in the medical issue area, where maybe health has measurable endpoints that aren’t stuck in this sort of sequential-feedback continua. Which suggests that, from a certain perspective, so does security… The perspective that comes to mind is that of authoritarian conservative political theorist Carl Schmitt. Need I say more?)

This could probably be written out mathematically to look more credible, but it wouldn’t be nearly as easy, fun, or readily understood by other humans.

How to Avoid Repeating Fienberg’s Mistake

My critique of Fienberg’s NAS polygraph report risks repeating his mistake. He effectively cut the graph on one line, erroneously concluding that polygraph programs would net harm security at National Labs due to the inescapable accuracy-error trade-off. I zoomed out to draw the graph showing multiple causal mechanisms instead: strategy, information, and resource reallocation all warrant their own modeling when we consider such programs’ net effects. (Notably, some of my dissertation research may have shown that police polygraph programs reduce police brutality without substantially affecting departmental diversity — consistent with important practical implications for the other causal mechanisms.)

But stopping there and calling it a net cost-benefits calculation would actually repeat Fienberg’s mistake — albeit with less of an excuse than he himself had, writing around the time of the causal revolution. We have to recognize that the graph has been cut — and ideally own that we ourselves have cut it. That resultant models are wrong but may be useful in generating insights and informing qualitative judgments. That science can’t tell us how to design our societies.

This rather changes the cost-benefits analysis that one can claim (or propose) to perform on Chat Control or any other proposed mass surveillance program.

That is, what we really we want to know as a society is how these programs net affect security. But that’s indeterminate, because it depends on where you cut the frame or the causal graph, as the case may be.

So no one is going to be able to calculate the net effects of proposed mass surveillance programs like Chat Control in terms of security the way the Stephen Fienberg and the National Academy of Sciences erroneously claimed to have done for polygraphs at the National Labs. Because we have to make a perspectival choice in deciding where to stop looking at outcomes as they pertain to security, even if we agree that security is the value or end we want to prioritize in contexts like this. Estimating the net effects of security programs on security is, in this sense, impossible.

Of course, there’s likely a better market for the impossible analyses. Here are perverse incentives (or perceptions thereof) again. People want to hear that they can figure out that their (un)favorite programs work or don’t work definitively. And we could pick empirical outcome measures to possibly determine that on those terms. (I did that, for example, when I looked at what effects police polygraph and other selection tools had on available measures of departmental diversity and brutality in national law enforcement survey data in my diss.)

But those measures would ignore this larger indeterminacy problem that we need to recognize, because it has significant sociopolitical implications. We really hate our limitations as puny humans, and want science to get us out of them. It can’t. We have to make value judgments and interpretive calls in deciding how to structure our societies.

Of course, that’s not a novel insight…

Woolsey on Striking the Balance

I used to hate the argument that policies have to strike a balance between liberty and security. It sounded, to naive empiricist me, like a cop-out. Why not actually measure program effects and do what works?

Well, because that literally makes no logically consistent sense (see above).

This is basically what former CIA Director Jim Woolsey told me in a 2009 polygraph interview, minus the grounding in causal logic:

Well, we face those choices all the time. That’s kind of what the American Constitution is all about. And I think it’s true that one has, sometimes, a conflict between national security and individual liberty. And we ought to make the best judgment we can about how to resolve any given conflict. But, and if polygraphs did not have the kind of false positive rate, when given to a large number of people that they do, if they did something imperfectly, but still reasonably well, I might, I don’t know, given the circumstances, strike a balance one way or the other, depending on whether we were in a cold war against a resolute enemy or whether we were in a relatively peaceful time. That was seemingly the case back in mid 1990s. Which are major foreign overseas were concerns were humanitarian. Are we going to help the Bosnians? Are we going to help the Croatians? Are we going to help the Rwandans? Are we going to help the Somalis? It was a different time really than either the cold war period before it or since 9/11. And the people strike those positions sometimes differently in different circumstances. But look in 1928 when we thought the world was sunny and no major problems, Harry Stimson, Secretary of State for President Hoover, shut down the State Department’s code breaking of foreign communications because he said — gentlemen don’t read one another’s mail. Now, Stimson was a great Secretary of War in World War II. He was a very conservative member of the establishment. He was not a flakey guy at all. But in circumstance of the times, even Henry Stimson, and even though these were not American’s liberties that were in question, these were communications between Germans, since gentlemen don’t read other people’s mail; he said — people strike these balances in different ways in different circumstances. What I keep coming back to on the polygraph is this large number of false positives and the fact that you can ruin a lot of people’s lives by the way judgments are made. I don’t know the circumstances because you made have to later answer a question — have you ever failed a polygraph? That can have a major negative effect on your life. So, I would be in favor of the continued use but in very limited circumstances. I think the FBI had it right back historically the way they have used it not for screening of all employees, but rather as an investigative tool. Hopefully we can find a better way. Hopefully we can do better at the polygraph for those purposes — as an aid to an experienced to the questioner — I’d be willing to see it used that way as long as all the assumptions were clear — the views were honest, etc.

In other words, circumstances change, norms matter, and doing what “works” in one context might not be right or even really work in another. You can’t calculate your way out of judgment calls, just like you can’t secure your way into a free society (or a healthy long-term relationship).

Who Cares?

In one reading, both sides of perennial debates on liberty versus security fail to recognize the indeterminacy of the issue. I see your (respective) existential threats, and raise you rejection of false security against the higher-level existential terror of epistemic uncertainty.

We have never been able to either determine whether “real causal autonomy” (Kevin J. Mitchell’s Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will, p. 299) exists, or functionally accept not knowing. Similarly, we have never known how to estimate net effects of state monopoly on use of force as they accrue to security considering its feedback problem with liberty. Scientific and sociopolitical discourse have never functionally accepted this indeterminacy. The latter doesn’t have to. But the former now must. It’s a logical implication of the causal revolution.

So what? One implication of this is that I didn’t accidentally kill the most popular argument against mass surveillance, as I recently wondered. I just tempered it by zooming out the causal graph to account for multiple mechanisms (and test iterativity, a topic for a future post). And now I’ve tempered the tempering by zooming out the picture again, and recognizing my pathetic inability to see the whole picture.

Maybe that humility is worth replicating.